Jeffco recommends closing 16 elementary schools

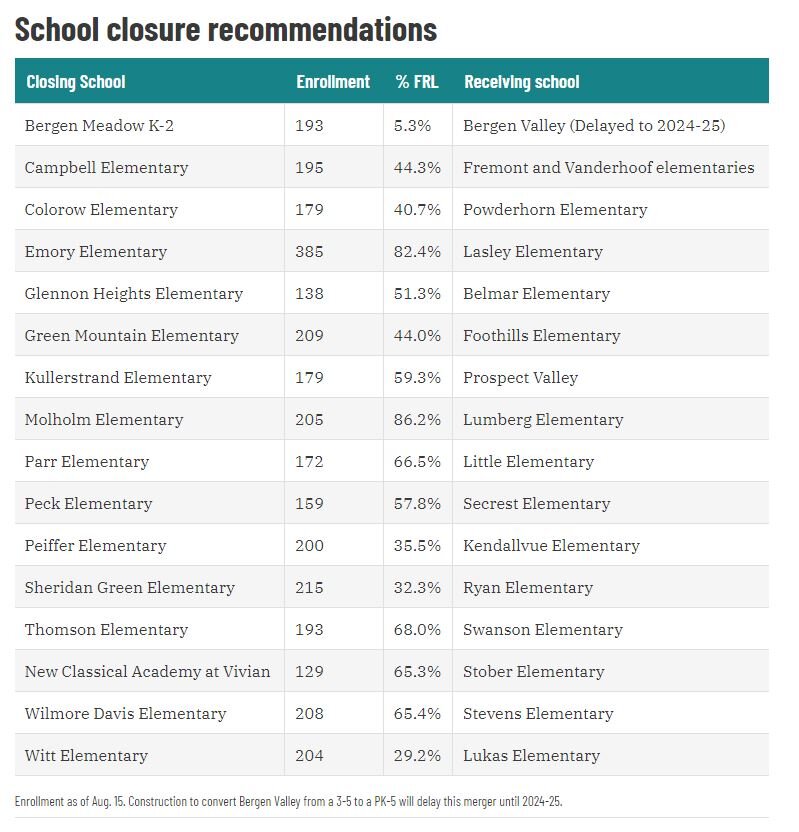

JEFFERSON COUNTY, Colo. — Jeffco has selected 16 elementary schools to recommend closing at the end of this school year.

All the schools have fewer students than they did a few years ago, and all but one had fewer than 220 students as of Aug. 15. All but one of the schools have a higher percentage than the district average of students from low-income families.

The district announced its recommendations Thursday and the school board will vote on the recommendations as a package on Nov. 10.

In the meantime, the district will host community listening sessions, but has made clear that the goal isn’t to hear which communities can best persuade the board to save their schools, but rather to talk about what families want to see in their new schools.

“I really am hopeful that our community will shift from wanting to fight the decision to wanting to be partners with us,” Jeffco Superintendent Tracy Dorland said.

In total, the district said the closures will displace almost 2,600 students and affect the equivalent of about 422 full-time jobs. The student numbers include the children of 27 families displaced when Allendale and Fitzmorris elementary schools closed in the past two years and who again will have to relocate. The district is assigning staff to work directly with those families.

Each of the schools identified Wednesday has fewer than 220 students, excluding preschool students, or uses less than 45% of their building’s capacity. And each of them is located less than 3.5 miles from another school with the capacity to absorb their students and still feed to the same middle and high schools.

So, along with every school proposed for closure, the district has named a nearby school that will absorb the boundary area and students of the closing school. In some cases, a third school will receive displaced students from programs for children with specific disabilities. All together, the closures will directly affect 38 schools, nearly half of the district’s 84 district-run elementary schools.

As far as staff, the district will help place teachers who are non-probationary, and will offer help to all others. For certified staff, the district is also offering to pay for them to get endorsements in hard-to-staff areas to make them more competitive for positions the following school year.

As before, parents may apply to enroll their children in schools other than the one assigned them.

District leaders want disappointed families to think of the transition as an opportunity for school communities to reshape the receiving schools to welcome new students and serve them and their families.

If the school board approves the closures, the district will form committees at each school to hear ideas from families and staff.

In the case of Emory Elementary, the principal already has pushed for its dual language program to move to Lasley, which is absorbing Emory students, though the type of dual language model could change.

Even if approved, the school closures will leave the district with 16 schools with fewer than 250 students or less than 60% of a building in use in 2023-24. That’s one-third the current number of schools that fit that criteria.

The district expects savings of up to $12 million may help reduce its budget deficit. This year, the district is drawing $28 million from its reserves to cover expenses.

The district has used $16.3 million from its 2018 bond to upgrade schools now identified for closure, but more recently put on hold $12.2 million in projects planned for small schools.

District says small schools are affecting learning opportunities

Still, district leaders have emphasized that closures aren’t just about the money, but about the quality of learning.

“We knew we were spending more money to support our small schools, but the amount of money is not leading to more robust programming,” Dorland said.

Lisa Mahannah, principal of Emory Elementary School, said that the recommendation to close her school didn’t surprise her, but was still hard to hear. The district has named principals who will lead the receiving schools. In Emory’s case, Mahannah’s assistant principal will move with the students, but not Mahannah.

Still, she said she’s had time to say her piece and knows that the district isn’t making these decisions lightly, so she’s focused on helping her families understand. She’s also a parent of a high school student in the district.

“This is impactful for everyone,” Mahannah said.

At Emory, with declining enrollment, she can’t provide everything her students need.

The school has students in dual language programming and students in English programming. But Mahannah said the school has been unable to pay for bilingual mental health or special education staff.

“The budget really drives how much support you are going to have for students,” Mahannah said.

And as dual language enrollment has decreased, classes split between two teachers per grade level have become smaller, while non-bilingual classes may have up to 30 students.

Emory has about 385 students on a former middle school campus with capacity to hold nearly 900 students.

Now, she plans to work the school year with Lauren LeMarinel, principal of Lasley Elementary, to plan how the merged campuses can serve students.

Lasley, about a mile from Emory, has about 291 students and uses about half of its school building.

As Lasley enrollment has declined, LeMarinel said, it has had fewer resources for students. Lasley shares art, music, and physical education teachers with three other schools. And this year, Lasley lost its after-school care program run by the Boys & Girls Club, which needed more students to support its work. The group decided to operate at just one school, Emory, in the region.

LeMarinel and Mahannah plan to ask if Lasley may bus students to Emory to participate in the after-school programming, as the two schools work on merging their support for students. They plan to find ways to share other partnerships too.

“We will do our best to make sure our community understands and we grow together as one,” LeMarinel said.

Enrollment was top of mind as Dorland took the job

A year and a half ago, Dorland had scant time to ease into her job. The board approved her contract in the same meeting right after discussing an emergency measure to close Allendale with little notice, because its dwindling student body made the school unsustainable.

Dorland immediately began examining enrollment and other problems behind abrupt closures.

“I was extremely concerned and shocked,” Dorland said. “I knew we had some issues. I had no idea the magnitude of the issue.”

Since 2017-18, the district’s total enrollment dropped more than 8% to about 78,473 last school year. At just district-run schools, the decline has been faster, about 11%. From 2019 to now, the district estimates it lost about 5,000 students.

While families sending their children to charter schools or other districts may play a small role, the major driver of falling enrollment is the decline in the number of school-age children in the county and the declining birth rate.

“We are very concerned that if we do not take action at this scope, we run the risk of having emergency closures in the next couple of years,” Dorland said. “It also leaves small school communities in a place of fear and anxiety wondering if they’re going to be next. We need to not be in a place of fear and anxiety.”

Dorland wants the district to address the enrollment challenges so that schools can focus on accelerating student learning and have more resources to do that.

Next steps include a look at secondary schools

After the vote in November, the district will begin examining enrollment and capacity at secondary schools, and possibly identify some for closure in the coming years. The district also is working on reevaluating the formula it uses to fund schools. Leaders want to hire experts to examine attendance boundaries and feeder patterns for elementary schools to middle and high schools.

Staff, like families throughout Jeffco, have experienced school closures in the past.

In Arvada, Principal Lara Wiant offered ideas on integrating campuses. Her school, Campbell, recently received students from Allendale and Fitzmorris when those schools closed.

She created a student ambassador program pairing each new student with a Campbell classmate who would offer a tour of the school, tips about who to go to for help, and who could sit with them during lunch.

Tara Peña, the district’s chief of family, school, and community partnerships, was an assistant principal of a school in Arvada that closed in 2010. She learned about her school’s closure at the same board meeting when her students and families heard the news.

She keeps that bad experience in mind as she helps the district shape its engagement and communication to families and staff that are affected. This year, principals were informed a few days ahead of everyone else, and instructional superintendents are helping them be prepared to support students and staff when they learn the news.

Mahannah said as a principal, she primarily wants parents to know that despite everything, her teachers are already working hard with students two weeks into the school year, and that won’t change. Just as most teachers worked through the difficulties of the pandemic, they will now too, she said.

“We’re going to go through a grieving process, but we’re going to show up every day,” Mahannah said. “Our teachers are amazing. They’re going to show up.”

Yesenia Robles is a reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado covering K-12 school districts and multilingual education. Contact Yesenia at yrobles@chalkbeat.org.