Looking ‘through the lens’ of Frank Muramoto at History Colorado

DENVER — In the late 1930s, as Hollywood studios were hesitating to shoot with color film because of its prohibitive cost, Frank Muramoto was using the relatively new technology to create home movies with his family in the San Isabel National Forest.

“These [cameras] are big monstrosities that he was carrying around for most of his career and his willingness to throw one of those over his back and hike up into San Isabel for the weekend is really impressiveh,” said Devin Flores, who helped curate “Through the Lens: The Photography of Frank Muramoto,” which is now on display at the History Colorado Center in Denver.

The exhibit — which made its public debut at the El Pueblo History Museum in the spring — covers the walls of the fourth floor mezzanine at History Colorado. “Through the Lens” uses Muramoto’s professional and personal photography to tell the history of everyday life in southern Colorado during an especially turbulent time in American history, particularly for Japanese Americans.

His descendants hope museum visitors see that at his core, Frank Muramoto was an immigrant with a dream.

“Immigration is so important to the U.S.,” said David Muramoto, Frank Muramoto’s grandson. “We need people who have dreams, who have vision, who have the willingness to work at it and make those dreams come true.”

According to the Library of Congress, more than 400,000 Japanese men and women came to the U.S. between 1886 and 1911. Muramoto, who had dreams of his own, was part of that group.

After moving to the U.S., Muramoto first lived in Colorado but soon left for Wyoming to work on the Southern Pacific Railway. He then traveled to Illinois and eventually worked as a houseboy for Frank Lloyd Wright. (Interestingly, both of Frank Muramoto’s sons would go on to be architects.)

“But then he went into a cutting edge technology — photography — which he had no background in at the time, but he had an idea in mind,” David Muramoto said.

“He said, ‘I'm going to go to Pueblo and I'm going to be a photographer there.’”

Muramoto owned and operated De Luxe Photography Studios in Pueblo from 1915 to until he passed away in 1958, when David was four years old. His professional photography included studio portraits, group photography and plenty of candid and nature shots.

A group of men dig in the sand near Beulah, Colorado.

Photo: Frank Muramoto, courtesy of the Pueblo County Historical Society

“That's what really makes this special, is as we travel the exhibit ‘Through the Lens’ — because it is literally through his lens — it is what he saw every single day and what he desired to capture, whether it was for posterity or whether it was just for artistic interest,” Flores said. “This immense collection of work that we have from him is truly a gift.”

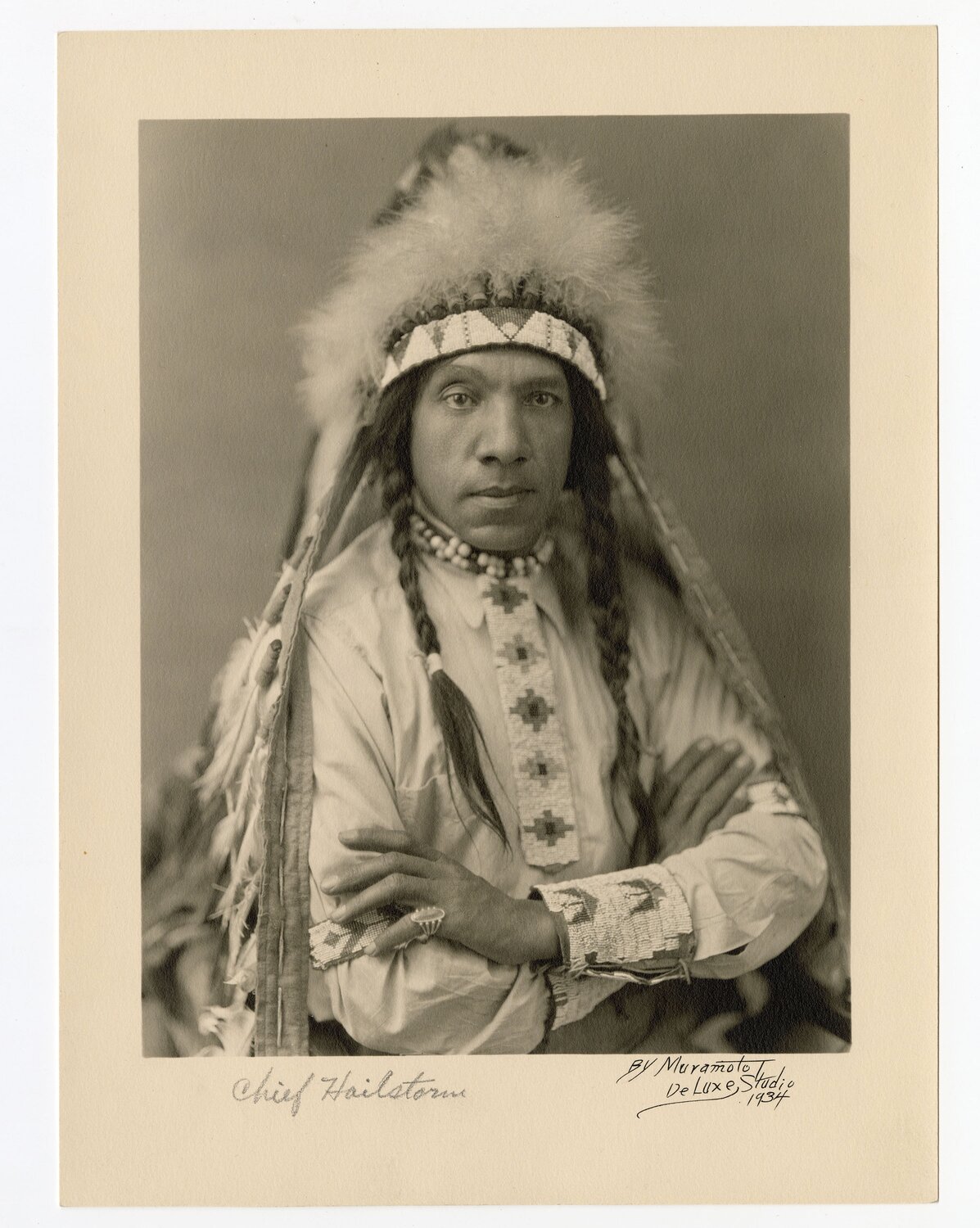

The large-scale prints of Muramoto’s photos at History Colorado are striking and feature a diversity of clients. His oeuvre includes photographs of Japanese immigrants, but also Native Americans, Black baptist groups, and more.

From a contemporary point of view, it seems Muramoto was a champion of diversity, and while that may have been true, David thinks there were other motivations at play.

“He would say, ‘that's not diversity, that's my living! I had to take pictures of everybody because I needed to. I needed the income,’” he said of his grandfather.

Flores thinks Muramoto deserves extra credit for the diversity of people he featured in his work.

“This is a time period where almost nobody owned cameras except photography professionals. So whenever people needed a photograph, they worked with a professional. Many of those professionals would not work with minority groups,” Flores said.

“They would not work with Asian Americans. They would not work with Latinos. They would not work with the Italians. And so it really sets Frank Muramoto apart, the fact that he was willing to take photos of anybody.”

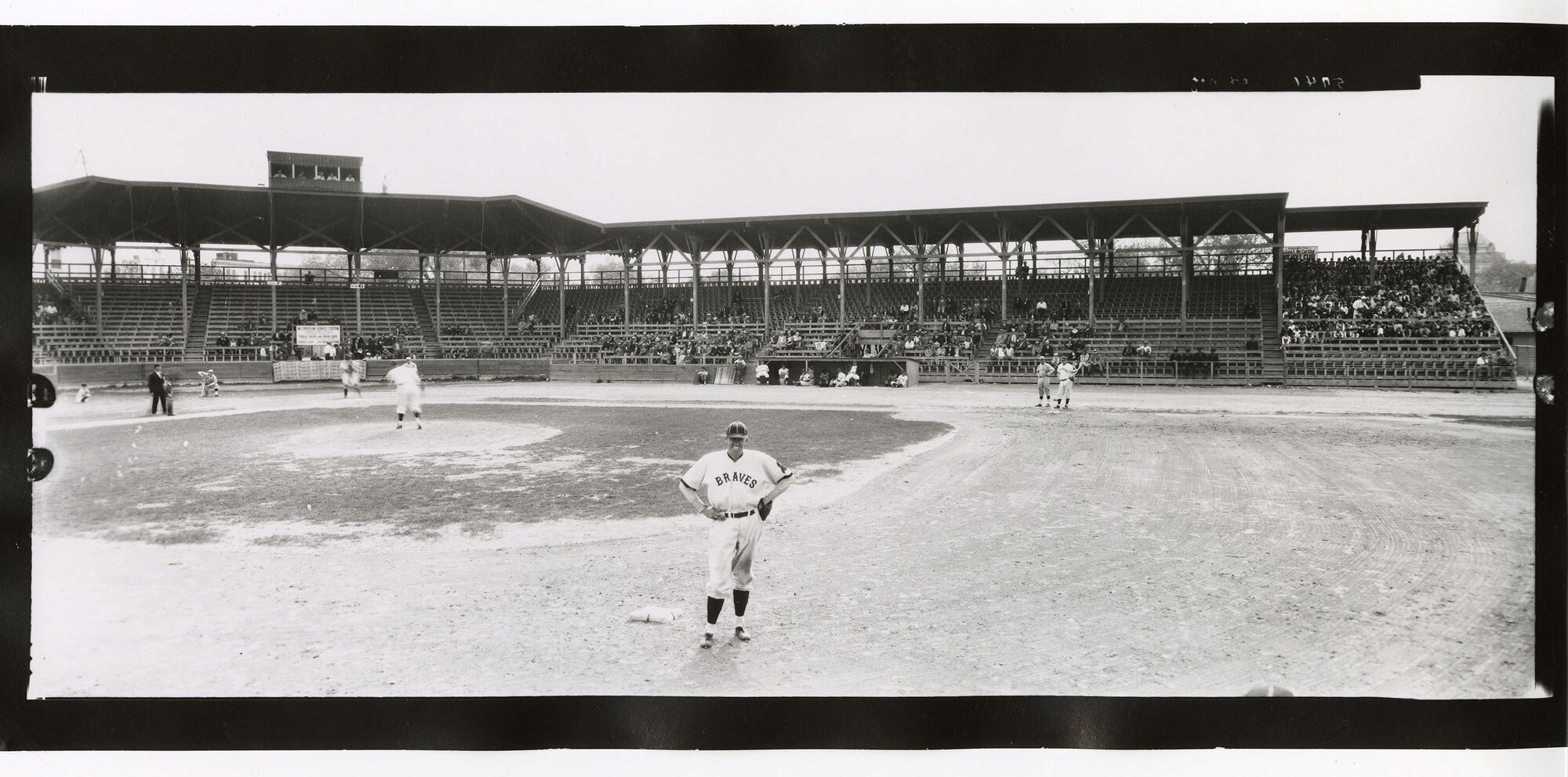

A Pueblo Braves baseball game. The Braves were a minor league baseball team in Pueblo from 1928 to 1932.

Photo: Frank Muramoto, courtesy of the Pueblo County Historical Society

According to Flores, the Japanese-American population in 1920 Pueblo was roughly 500 — about 1 in 60 people were of Japanese heritage. At the time, Pueblo was the second-largest city in Colorado, but the Asian American community would dwindle in numbers after a series of devastating events.

In 1921, the “great Pueblo flood” destroyed much of the downtown area, including businesses owned by immigrants. The total death toll remains unknown, but conservative estimates indicate that more than 100 people died. The United States entered the Great Depression by the end of the decade, which saw many people leave Pueblo for better economic opportunities in Denver, and just two years after the end of the Depression, Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor. In response, Japanese Americans were incarcerated in camps like Camp Amache.

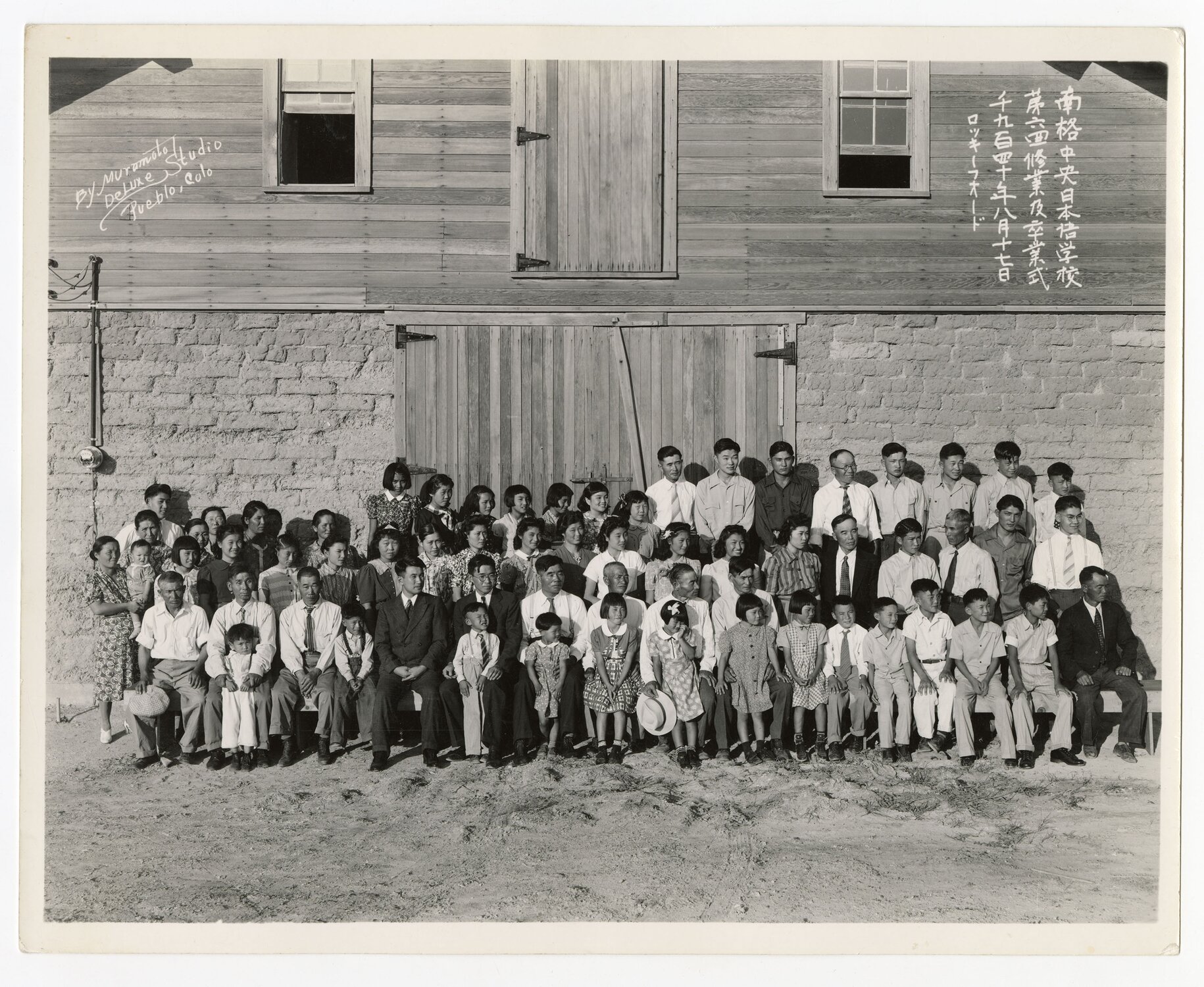

Flores said he didn’t know about the Japanese Language School, pictured here in Rocky Ford, Colorado in 1940, until he explored Muramoto’s archives.

Photo: Frank Muramoto, courtesy of the Pueblo County Historical Society

Muramoto avoided the fate of so many other Asian Americans between the 1920s and 1940s. De Luxe Photography Studios survived the Depression and Muramoto was not interned during World War II. In fact, he worked as a translator on the Pacific Front and gathered intelligence for the U.S. Army.

But as David Muramoto said, “there's nothing like atomic bombs and world wars to break family ties.”

After World War II, Japanese Americans prioritized assimilation over the preservation of Japanese culture, David Muramoto said. His grandfather’s photographs, however, allow him and his family to connect with their roots.

“My Japanese [vocabulary] is very, very small,” David Muramoto said, “and yet I really have a strong feeling for my culture and all these pictures that my grandfather took, he's almost bridging it over time for me.”

As immigration remains a key issue in American politics, David Muramoto hopes that U.S. policy doesn’t preclude the next Frank Muramoto from fulfilling their dreams.

“There's so much value in immigration. And I wish that we, as Americans, had the ability to learn from the past a little better than we have,” David Muramoto said standing in front of his grandfather’s exhibit.

“This is kind of a tribute to all of the immigrants who came to the United States in search of a dream. And they found it. And other people can do that, too.”

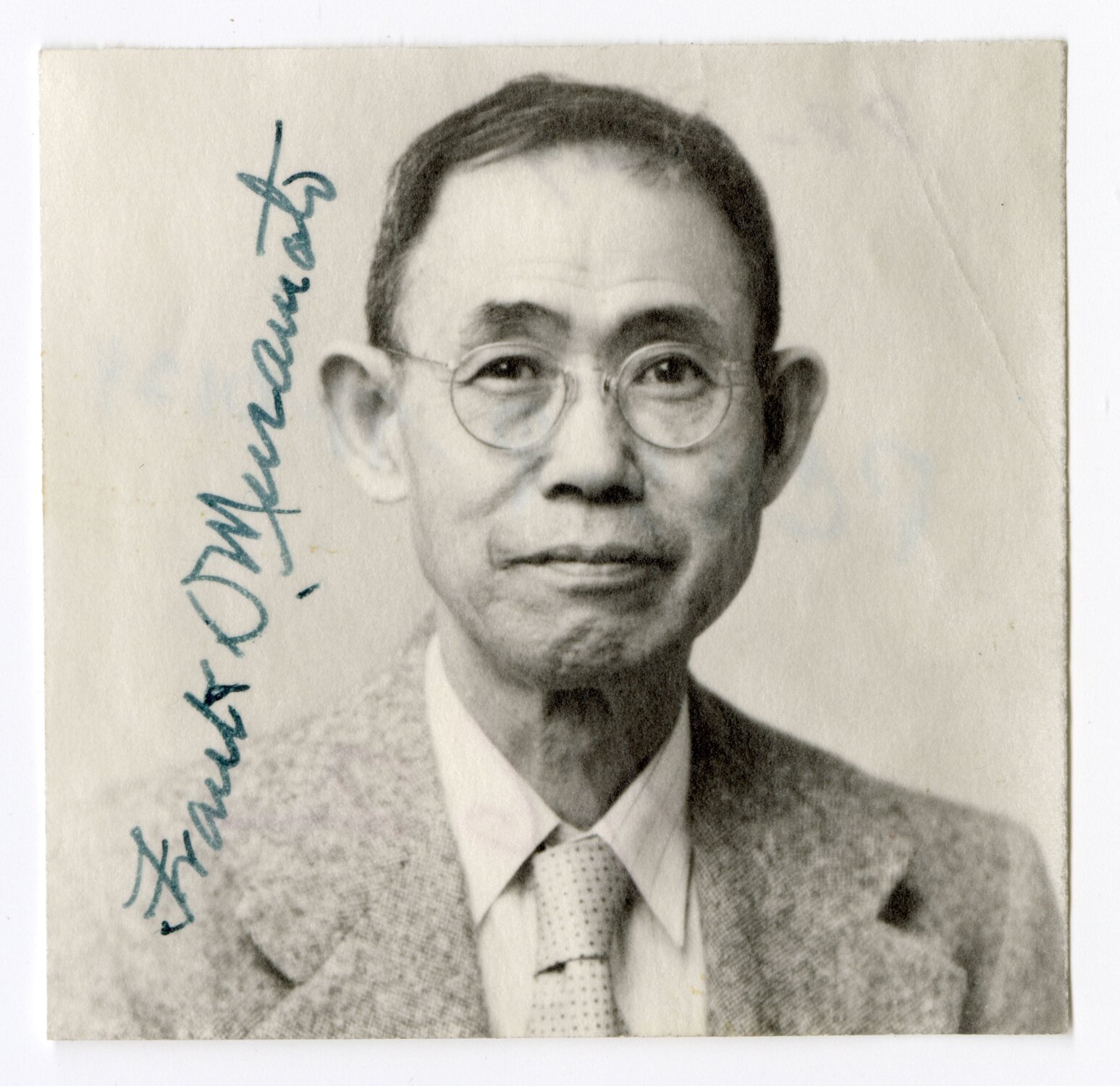

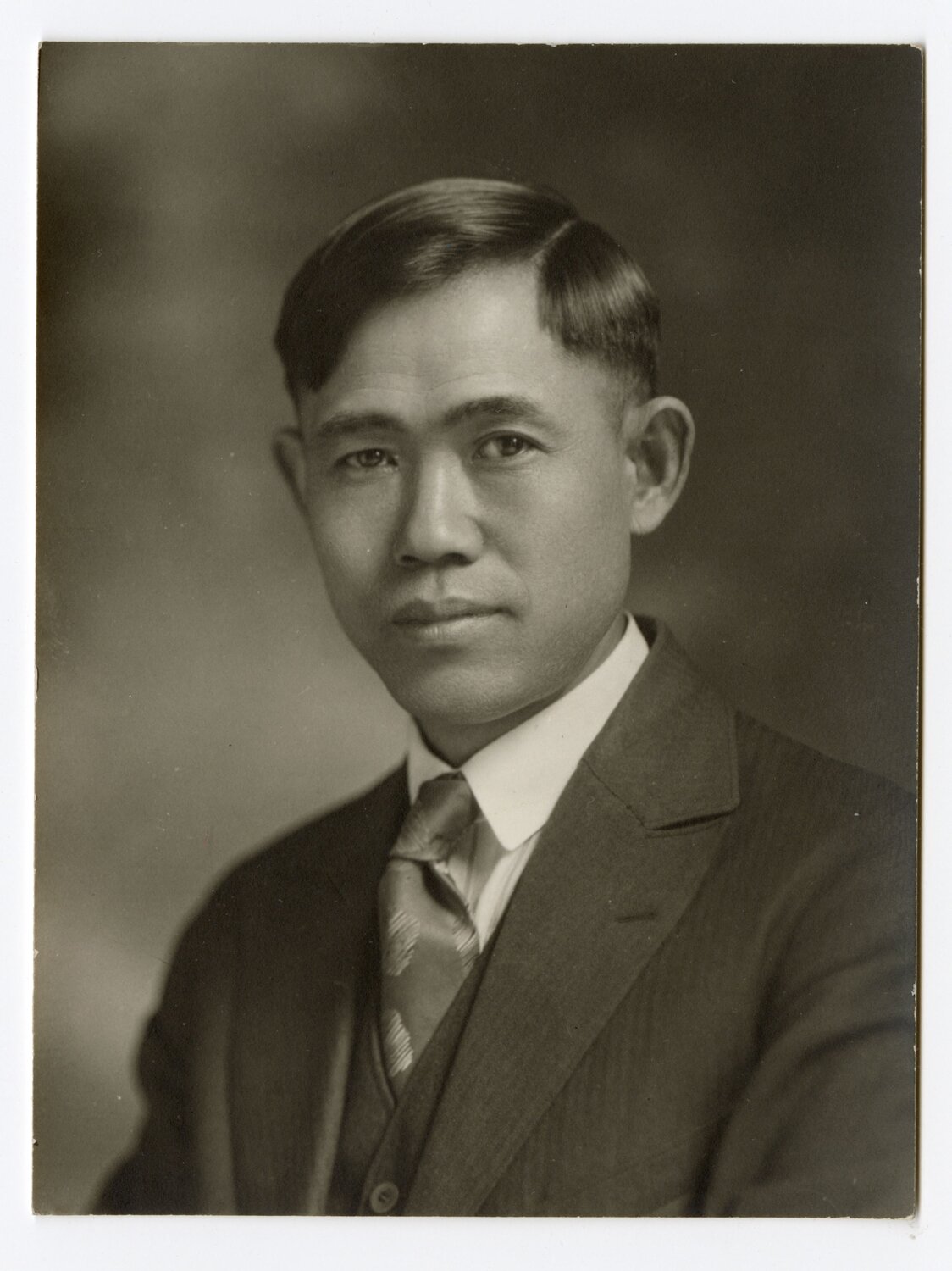

A self portrait of Frank Muramoto with signature.

Photo: Frank Muramoto, courtesy of the Pueblo County Historical Society

Kyle Cooke is the digital media manager at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach Kyle at kylecooke@rmpbs.org.

Julio Sandoval is the senior photojournalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach Julio at juliosandoval@rmpbs.org.

A photo of Chief Hailstorm, captured in 1935.

Photo: Frank Muramoto, courtesy of the Pueblo County Historical Society

A portrait of Frank Muramoto.

Photo: Frank Muramoto, courtesy of the Pueblo County Historical Society