New generation of research targets racial disparities in cystic fibrosis diagnosis and treatment

DENVER — For decades, the conventional wisdom on cystic fibrosis, a genetic disease that causes mucus to build up in the body’s passageways, held that it mostly affected white people. New research out of Colorado aims to address the racial disparities in diagnosing the disease and saving the lives of everyone who lives with it.

“For years and years and years, really up until the last five years or so, CF was always described as a disease that only occurred in people who are white,” said Dr. Jennifer Taylor-Cousar, a pulmonologist at National Jewish Health who specializes in cystic fibrosis and pediatric lung disease.

“And that misperception has created all kinds of downstream effects that have led to health inequities,” said Taylor-Cousar.

Taylor-Cousar said because of racial bias, physicians will identify classic signs and symptoms of CF but often misdiagnose the patient if they are a person of color. The dangers of misdiagnoses can lead to worsened symptoms or potentially death, she said.

Conner Holmes III, who is Black and lives in Denver, lives with cystic fibrosis. Though he was diagnosed as a child, Holmes said he was denied medical care for his cystic fibrosis later in life because of his ethnicity.

“I was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis when I was an infant, and then they told my parents I wouldn’t live to be one year old,” Holmes said.

“Every doctor that I went to, when they found out I have CF, ‘No, you don’t! No, you don’t! It’s impossible, you’re an African American, you can’t have it, you can’t have it!’ And so, after they then ran all their tests, ‘Wow! I guess you do!’”

Holmes said it got “old and frustrating” when doctors did not believe he suffered from cystic fibrosis.

“Just like being Black, it gets old trying to accept the disrespect and that lack of understanding and the [being], put in a box,” he said.

Mariana Valencia, a Latina woman from New Mexico, knows the seriousness of CF all too well. Her brother, who lived with CF, passed away from complications of the disease in 2012.

“This disease is quite cruel sometimes … and we need people in our corner,” Valencia said.

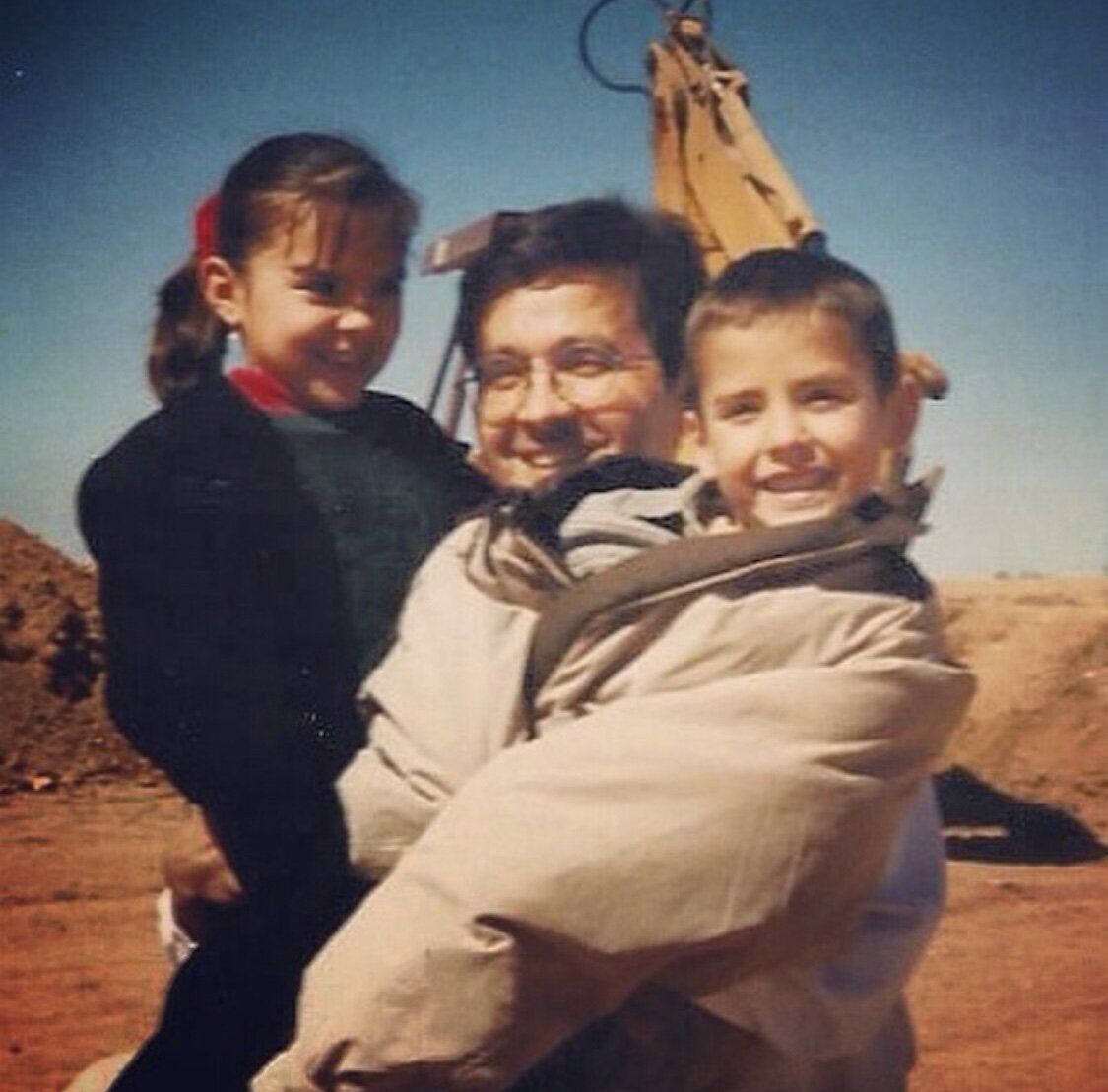

Mariana Valencia and her brother, who also had CF, with their father.

Photo: Mariana Valencia

Valencia received a lung transplant three years ago. Before her transplant she carried out extensive daily routines to get ready for the day. Although she began in the morning, her preparations would last into the afternoon.

Valencia would start her days with nebulized medications to help open her airways and thin out the mucus in her lungs. Then, she would take an antibiotic. She also wore a vest, called a High-Frequency Chest Wall Oscillation vest, that created rapid inflation and deflation to create pressure on her chest. This pressure helped separate the mucus from her airway wall so she could cough out the mucus. Valencia said mucus in the lungs can create a breeding ground for bacteria, making her ill.

Although things have been easier since her lung transplant, Valencia still lives with CF.

She said her biggest motivation is her family. “I want to be around, I want to see my parents live in peace,” Valencia said.

“I want a boring [and] uneventful life, that’s what I strive for,” Valencia said. “Kind of tired of the, you know, surprises and adrenaline rush, I’ve had enough of that. Ride in an ambulance enough times and you will… you will get tired of it, too.”

Clinical research on CF

Black and Hispanic people with cystic fibrosis have a higher risk of death before the age of 18 compared to white people with cystic fibrosis, according to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation .

In the U.S., close to 40,000 children and adults live with cystic fibrosis and, of that number, approximately 15% identify as racially or ethnically diverse, according to 2021 data from the foundation.

Taylor-Cousar currently co-leads the MAYFLOWERS study, which examines how certain CFTR (Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator) modulators affect pregnant people with CF. One of the side effects of the disease, said Taylor-Cousar, is infertility, and the study has helped more than 600 women become pregnant.

Taylor-Cousar said in the United States, a pill form of the CFTR therapy, called Trikafta, has been shown to be effective at preventing complications for people with specific mutations of the CF gene. But, although the medication positively affects about 90% of people, she said, disparities remain.

“Unfortunately, that last 10% of people are over-represented by people of color,” Taylor-Cousar said. “But again, we’re having these conversations now so we can pay more attention to the mutations that occur in people of color and try to develop therapies that are specific for those mutations. Still, also, we’re trying to find a cure for CF for every single person with CF.”

Hope for the CF community

“You know, one of my favorite authors as is the case for many people is Maya Angelou and one of the things she said was, ‘Develop enough courage to stand up for yourself and then stand up for somebody else,’ And so I think that’s what I really take to heart and want to do for other people,” said Taylor-Cousar.

Dr. Taylor-Cousar winning an ATS award for achievement with research on cystic fibrosis.

Photo: Jennifer Taylor-Cousar

Last year, Taylor-Cousar said gene therapy trials have already started to help “correct” people with CF. These trials have shown that for the first time in CF research, medical doctors have successfully introduced a corrected gene into the lungs of people with CF, which will improve their overall health.

“I think another positive for the CF community is, it’s one of the most amazing success stories in medicine because its shows what can happen when people with CF and their families and researchers and clinical care teams get together to move a disease forward,” Taylor-Cousar said.

“Often times in medicine, and I’ve seen in other disease states, there is a lot of competition and there isn’t a partnership with the CF community, the patients and their families. But when you get everyone together, you can really create magic, and that’s what we’ve been able to do in the CF community.”

At National Jewish health, Holmes was under the care of Dr. Steven Lommatzsch, another CF specialist. Holmes said Lommatzsch listened to him rather than disregard him like many other doctors had. Since then, Holmes' lung capacity has increased from 18% to 38% over the course of six months.

“You talk about praising God… and I know that God does miracles, but I also know God will send you someone or something to help you, and this someone was Steven Lommatzsch,” said Holmes.

Valencia said CF is mentally and physically draining, and at times, she might not be able to respond to messages when her friends contact her, but that doesn’t mean she isn’t appreciative of the love shown to her.

“Don’t give up on your friend with CF if you have one. We’re great people you know? We might have our moods and we might not always answer our phones because we’re going through a lot, but we need our friends,” she said.

Valencia said she started speaking up about her CF story because someone spoke up and advocated for her.

“That’s what I want people to do. I want people to advocate for those whether it's CF or whatever your battle is, advocate for those people,” she said. “Because we need as many people as we can get in our corner. We won’t be able to do this without getting the rest of the population on board.”

Lindsey Ford is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. lindseyford@rmpbs.org