Colorado’s bald eagle population is booming in urban areas. The state is trying to figure out why.

DENVER — It’s no secret that the human population on Colorado’s Front Range is expanding. State officials predict that in the 10-year range from 2019 to 2029, Colorado will grow by more than 800,000 people, with about 87% of them settling in the Front Range.

More perplexing, however, is that another population is growing in that same densely populated urban corridor: bald eagles.

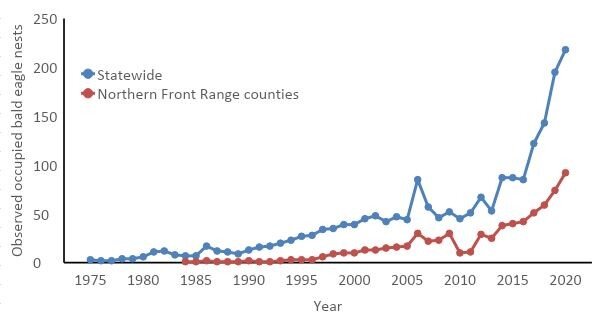

According to Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW), the whole state of Colorado had just three known bald eagle nests by the end of the 1970s. Today, the state is home to over 200 nests—some in “unconventional” locations, like the Front Range. This could explain why people who frequent Denver's City Park have become accustomed to seeing bald eagles in the area.

"We know that our population of eagles has increased in this area," said Reesa Conrey, an avian researcher with CPW. "And we know that our population of humans is also increasingly very rapidly."

Colorado Parks and Wildlife announced this week that they have embarked on a four-year study to learn why these eagles—the national bird of the United States—are settling in urban areas that are often disrupted by construction and other human activity.

For our new bald eagle study, we are deploying 25-30 of these transmitters on bald eagles. The transmitter data will allow researchers to intensively monitor habitat use & eagle movements year-round, during both the breeding & nonbreeding seasons.

— CPW NE Region (@CPW_NE) July 13, 2021

Story: https://t.co/Dn7xo4pQtR pic.twitter.com/KCp0sAA4yW

Other agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies (BCR) are participating in the study, which will be the “most comprehensive bald eagle monitoring project ever done by CPW,” according to a news release.

According to CPW officials, Colorado’s eagle population declined in the mid-20th century due to human disturbance, loss of habitat, and DDT, a pesticide that poisoned the birds and made their egg shells extra thin. The egg shells “often broke during incubation or otherwise failed to hatch,” according to the USFWS.

DDT was banned in 1972, and the eagle population nationwide rebounded as a result to the point that in 2007, the iconic birds were removed from the endangered species list. (Eagles are still protected under both the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.)

Despite all the development on the Front Range since the 70s, the state has also made it an easier place to settle with the construction of reservoirs.

The first bald eagle nest in the Front Range was established in Barr Lake State Park in 1986, Conrey said. Storms destroyed that nest and six others over the course of many years, including a nest in 2021. The eagles are currently rebuilding their nests at Barr Lake.

The first eagle nest in the Front Range was established in Barr Lake State Park in the 2000s, Conrey said.

For this research project, CPW is using GPS transmitters to track the eagles in the northern Front Range.

According to CPW, “results from the monitoring effort will be used to model the bald eagle population trajectory and expected impacts of predicted future land use change. Biologists will then make data-driven recommendations on minimizing and mitigating disturbances of the bald eagle’s environment essential to its survival.”

Researchers hope the data will help them identify ways to preserve and develop ideal eagle habitat in urban areas as well as better understand the birds’ tolerance to human activity.

Conrey said she also hopes the results will help the state give "better recommendations to developers, consultants [and] the general public to make sure that eagles are being managed properly and will continue to be successful here."

You can read more about the research project here.

Kyle Cooke is the Digital Media Manager at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach him at kylecooke@rmpbs.org.

Clarissa Guy is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at clarissaguy@rmpbs.org.