Colorado veteran uses social media to amplify the voices of Afghan people

DENVER — Although the U.S. has withdrawn from Afghanistan after two decades of war, the turmoil continues for thousands of Afghan people trying to leave the country, which is now under Taliban rule.

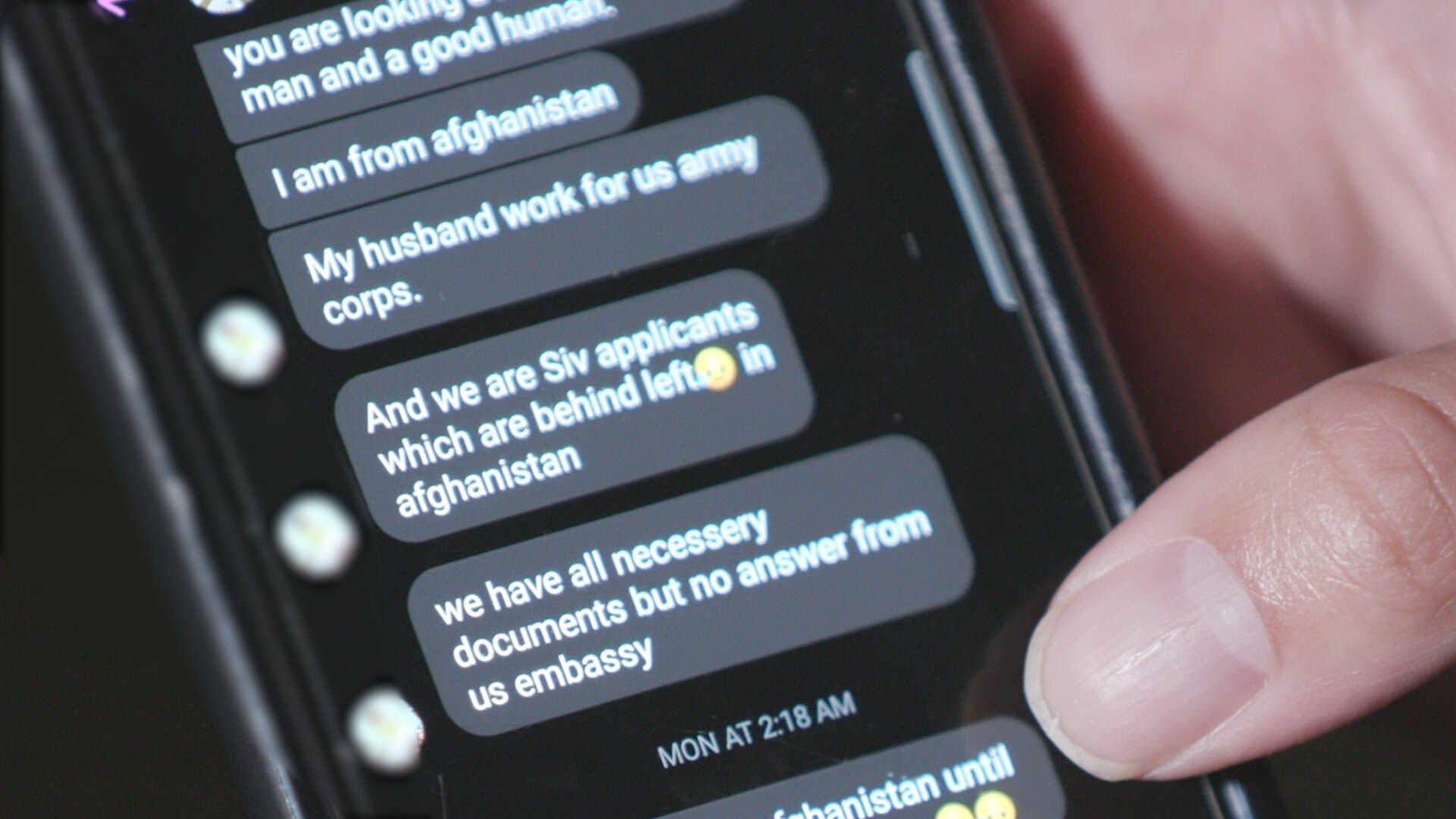

“I’m terrified right now. I’m scared. If the Taliban catches me, they will not leave me alive,” a man named Abdul told Rocky Mountain PBS. To protect his identity, Rocky Mountain PBS is only using Abdul's first name. He spoke with us via Facebook Messenger from an undisclosed location in Afghanistan.

Abdul is one of the thousands of Afghans once employed by the U.S. Government as interpreters, contractors and translators. After the U.S. Embassy closed and the last of the American troops left, Abdul and his family went into hiding, fearing retaliation from the Taliban.

"I don’t know that after this interview is over, that I will be alive or not," Abdul said. "I don’t know what to do.”

Like Abdul, many Afghans employed by or on behalf of the U.S. government have applied for a Special Immigrant Visas (SIV) and are still awaiting approval. It can take years to complete.

“I have been waiting for my SIV approval since 2018,” Abdul explained. “I have an open SIV case, and it’s under review at the U.S. Embassy, but the embassy is closed."

Without the visa, Abdul and his family have no choice but to stay in Afghanistan. They remain in hiding.

“I don’t have any money. I don’t have any supporters,” Abdul said. “My family and I are living with my father-in-law. He gave us food and water. He can go outside, but I cannot go outside.”

The fear is evident in the recorded voice messages Rocky Mountain PBS exchanged with Abdul. His three sons—ages 6, 10, and 12—and his wife were close by, even adding to the conversation.

One of Abdul’s sons, sounding confused and scared, wondered aloud: “Why can’t I go to school?"

Abdul said he doesn’t have anyone to help his family safely leave Afghanistan. But he does have a friend: American veteran Angel Guma, who knows Afghan culture.

Colorado veteran maintains a connection with Afghan allies and commits to sharing their voices

The Facebook page Operation Rescue Afghan and Iraqi Interpreters has grown to over 1,000 followers since mid-June.

“I started it when Biden announced [the troops' withdrawal], and things started going wrong,” Guma told Rocky Mountain PBS during an evening interview on September 14.

The goal of the group is to create a community of volunteers and activists that believe in helping Afghan allies come to the U.S. It is also Guma’s way to keep to his promise from nearly a decade ago: “I will be with them till the very end.”

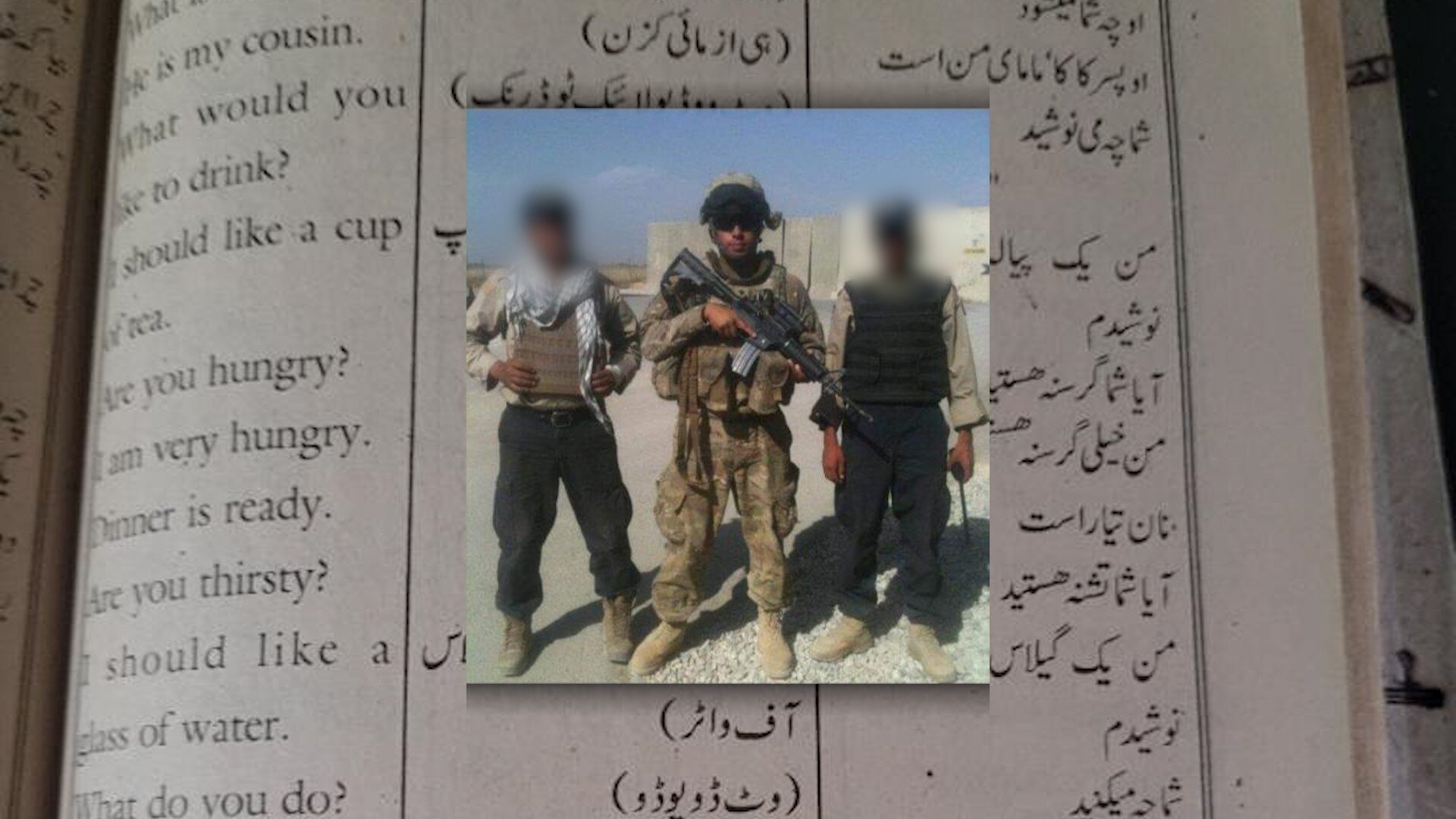

The Afghans are people he grew to respect during his military service at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan.

Guma has a full-time job and is dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He explains that sleep is scarce for him. Still, Guma has deep conversation with many Afghan allies like Abdul every day.

“There is an Afghan brother who has been messaging me for weeks, begging me to help him," Guma said. "And one morning, he told me, ‘Look, my brother is dead,’ and he showed me a photo of his brother’s mangled body. The Taliban killed his brother.”

Guma, originally from Chicago, now lives in Colorado. From 2011 to 2012, he served in the US. Army with the 785th Military Police Battalion, where he was stationed at Bagram’s airbase. His unit’s mission was to help train Afghan military police. During his time in Afghanistan, he learned to speak Dari, one of the most widely-spoken languages in Afghanistan.

Guma explained that people in Afghanistan cannot just get on a plane and leave the country.

"There is no way anyone could come and go from Afghanistan on land without at some point crossing that highway," he said. "The Taliban knows this. The country is shaped like a ring and linked by one highway. All major cities are located around this one highway. I’ve been told there are dozens of devices and special checkpoints along this highway, making it impossible for anyone to not run into the Taliban.”

Guma continued: “The Afghan people are sitting ducks. There’s this idea that many Americans seem to think that people in Afghanistan live in a world of options. That is not true. Americans think it is easy for them to get up from their village and go somewhere else. That is not true."

For Guma, there is a feeling of helplessness when it comes to helping his friends in Afghanistan. He hopes by creating his Facebook group and speaking with the media, he will find more opportunities to help people trying to leave Afghanistan.

“My hands are tied; I’m helping my Afghan friends by appearing on Rocky Mountain PBS," he explained. "I have tried just about every avenue to get people the care they so desperately need."

[Related: How you can help Afghan refugees arriving to the U.S.]

What is next for Afghan allies? Congressman Jason Crow responds

So, what is next for Afghans looking to leave their home country? Is there any hope?

On a local level, U.S. Rep. Jason Crow (D-Aurora) and his team held a Community Town Hall Webinar on Monday, September 20, to discuss just that. Crow’s office has put together list of Afghanistan Evacuation Resources. Crow also noted that U.S. citizens and Afghan people who need help leaving Afghanistan can fill out this form to request help from the U.S. embassy.

Congressman Crow reiterated that his office sympathizes the hurdles people like Abdul are facing.

“The SIV Program is an enormous challenge. It was a challenge before the collapse of the Afghan government. On average, it took an applicant about 800 days to be processed. So there was a huge backlog prior to the fall of the government,” said Crow, a former Army Ranger who served in Afghanistan. “In mid-August, there were more than 20,000 people in the applicant pipeline. That’s just the applicants themselves. That’s not even including their family. So, on average, there are about three family members per principal applicant. So there were well over 80,000 people who were in that pipeline.”

Crow acknowledged one of Afghan allies' biggest concerns: the possibility that the Taliban is using U.S.-made biometrics. As the Associated Press reports, these biometric devices contain fingerprints, eye scans, and biographical information of Afghans who assisted U.S. troops. In the hands of the Taliban, there are fears the technology could be used to target U.S.-aligned individuals like Abdul.

“The short answer is we don’t know if the Taliban is using U.S. biometrics. We know to be true that these Afghans who aided with us, fought with us, and served with us remain at tremendous risk," Crow said. "These Afghans have been targets of the Taliban for years, basically since day one of this conflict over 20 years ago."

[Related: A historical timeline of Afghanistan]

Related Stories

Crow noted that the resources he and his office compiled are only the beginning to help Afghan allies.

“First of all, this I’m going to be clear, this story is not over," he said. "We have a continuing obligation to these thousands of families who are still in Afghanistan. My office alone has over 3,500 requests for evacuation that we continue to work on. So, the areas of hope here are that we have allies and partners who are still operating and have access to Afghanistan from Qatar, Turkey and other countries. We will continue to work with those folks to provide safe passage to provide charter flights out of commercial flights and security around the airport.”

Lindsey Ford is a multimedia journalist at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at lindseyford@rmpbs.org.

Jennifer Castor is the Executive Producer of Multimedia Content at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at jennifercastor@rmpbs.org.