Colorado’s new Universal Preschool program released its data. Here’s what we found.

DENVER — Colorado’s Universal Preschool program launched last year after landmark legislation, House Bill 22-1295, passed in 2022. The program, popularly known as UPK, helps fund preschool for every Colorado child the year before kindergarten. UPK is also available for some three-year-olds.

UPK works by issuing participating providers a stipend to cover the cost of tuition for the UPK slots. According to the state, Colorado now ranks seventh in the nation for providing pre-school access to four-year-olds, thanks in part to UPK. But parents and educators say there are areas where the program could provide more support and guidance.

In September, Rocky Mountain PBS filed a Freedom of Information request with the State of Colorado to review the impact of the state’s pilot program. Our analysis confirmed that more four-year-old children are being served.

However, this year, when the state transitioned away from its targeted pre-school program, Colorado Preschool Program (CPP), to a universal one, the pool declined of three and four-year-old children with the highest needs who qualified for additional support.

As a parent on Medicaid raising three-year-old twins diagnosed with autism, Tinsley Ore said she has not received nearly enough state support this year to meet her family’s needs.

Ore lives in northeast Denver and has only one UPK option, Highline Academy Northeast, available to her kids in the Green Valley Ranch neighborhood. The program offers only three hours of support each day.

Caroline and James Bogan with their mother, Tinsley, at Highline Academy.

Photo: Lizzie Mulvey, Rocky Mountain PBS

“I’m going to cry, it’s been so awful,” Ore said.

Every day at 11:30 a.m., she spends an hour driving her twins from the Highline Academy to behavioral therapy at Soar Autism Center in the Park Hill neighborhood.

“It’s right in the middle of my day so I can’t get anything done,” she said. Ore picks her kids up at 4:30 p.m., right at rush hour, takes them home, cooks dinner and puts them to bed.

“Because of the three hours [of UPK] a day, I haven’t been able to work an actual job,” she said. She had to quit stable employment as a social worker to become a full-time caretaker.

“I didn’t want to quit...I wish I could work forever in the social work field,” she said.

Caroline and James Bogan with their mother, Tinsley Ore, at home in northeast Denver.

Photo: Lizzie Mulvey, Rocky Mountain PBS

She finds it hard and frustrating to not have more options or support with transportation.

This year, her three-year-olds receive about 10 hours of free preschool a week. Under the former state preschool model, Colorado Preschool Program (CPP), they would have been eligible for 20 free hours.

After the pandemic, Ore said, her children need the socialization and cognitive stimulation that preschool offers even more.

Tinsley Ore picks up her children, Caroline and James, from Highline Academy.

Photo: Lizzie Mulvey, Rocky Mountain PBS

According to Lisa Roy, the executive director of Colorado’s Department of Early Childhood Education (CDEC), three-year-olds are not part of the Universal Preschool Program because CDEC sends funds to school districts for them to manage.

Practically, what this means is that school districts decide which three-year-olds — beyond those with an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) as mandated by the state — they will serve. The district also decides whether to keep all of the UPK slots or share them with other local child care providers.

However, Section 26.5-4-204 of the law says that the purpose of the Colorado universal preschool program is to “provide access to preschool services for children who are three years of age, or in limited circumstances younger than three years of age, and are children with disabilities, are in low-income families, or lack overall learning readiness due to qualifying factors.”

Three-year-old eligibility was also advertised as part of the UPK application on CDEC’s website.

Whether they are a part of UPK or not, some three-year-olds can qualify for free preschool hours if they are low-income — that’s defined as below 270% of the Federal Poverty level, or a gross income of about $82,000 for a family of four — or have a qualifying factor, including having limited English proficiency in the home, being unhoused, having a child in foster care or having a child that’s eligible for special education with an IEP.

“This is due to financial constraints caused by the three-year-old funding being a set dollar amount tied to 2022-2023 CPP spending, and not increased annually for inflation,” said Ian McKenzie, public information officer for the Colorado Department of Early Childhood.

In other words, the department won't necessarily have the budget to cover all three-year-olds in the state.

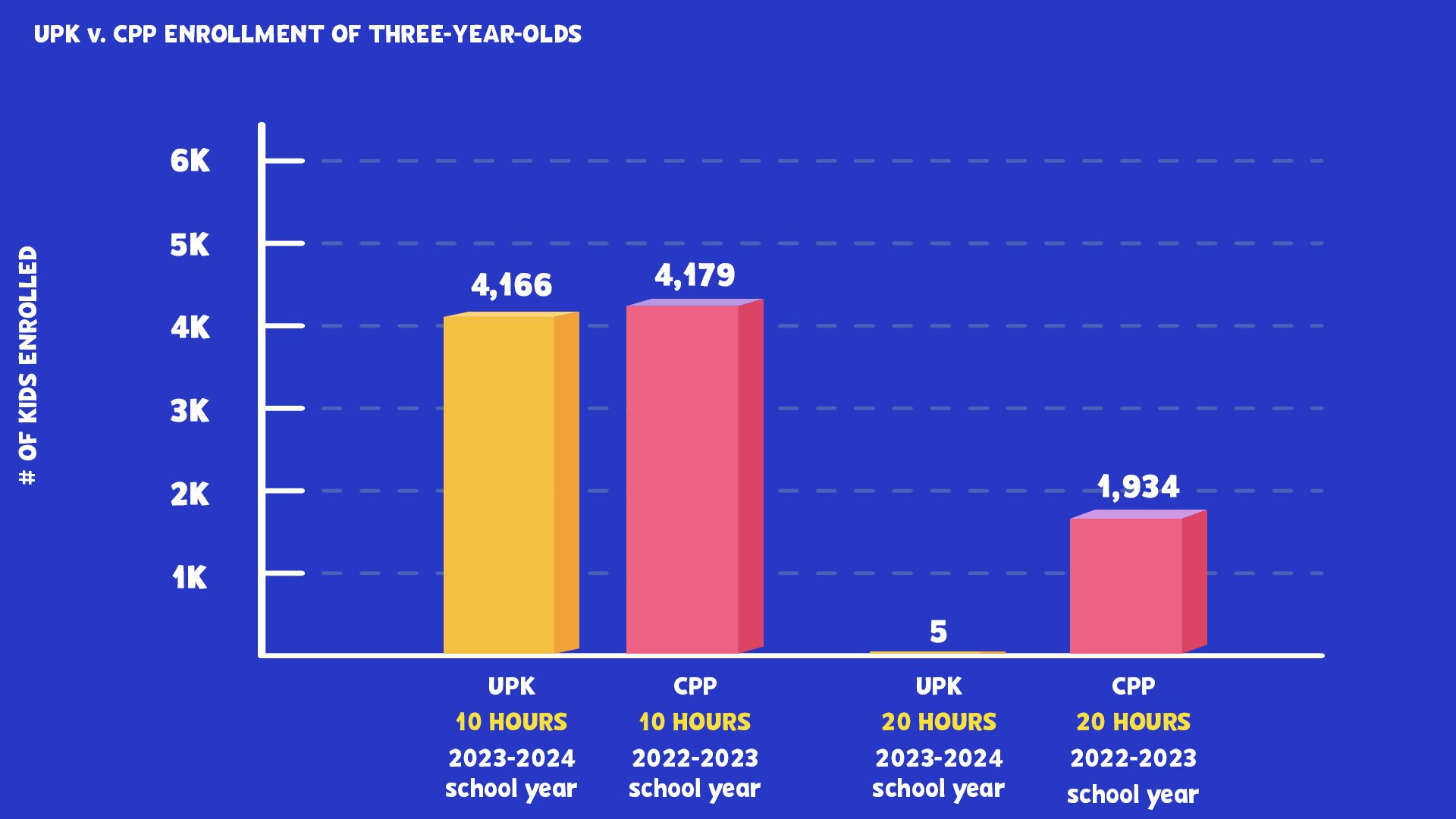

In total, 4,166 three-year-olds received 10 hours of free pre-school during the 2023-2024 school year, on par with the previous school year, when 4,179 three-year-olds received a half-day, or 10 hours of free preschool a week.

In the 2022-2023 school year, under CPP, 1,934 three-year-olds who met certain risk factors received an average of 20 free hours each week.

This current school year, under UPK, only 248 three-year-olds receive 15 free preschool hours with just 5 children receiving more than 15 hours preschool hours each week.

Although the mandatory hours have remained relatively the same, for low-income parents who work full-time, UPK did not guarantee any additional free hours for three-year-olds. This has meant that families with students in full-day programs have to find a way to make up the difference between the subsidized hours and the full-time tuition.

Confusion about which students are eligible for which subsidies

Throughout the 2023-2024 school year, parents consistently expressed confusion about their subsidies, particularly for three-year-olds.

The amount of UPK funding allotted annually to three-year-olds is distributed by CDEC to school districts for them to manage, said McKenzie, public information officer for the CDEC.

The state’s decision to let school districts decide eligibility has contributed to the confusion.

Families are accustomed to visiting preschools in-person, at open houses and other events, and working directly with the school to enroll.

The online application “was a very different process, and is still a huge learning curve,” said Lora White, an administrative assistant for the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Lincoln Early Childhood Council (CKLECC), which represents rural counties in the Eastern Plains.

“I don't think it was well explained in the beginning by the state or by us to the families,” White said.

Child care access, a consistent problem for rural communities, has persisted under UPK. Families we spoke to in less populated areas of the state felt that they had far fewer preschool options for UPK.

Nonetheless, when comparing larger counites — above the median population size of 8,000 — to smaller counties (with fewer than 8,000 people), enrollment rates were about even. Enrollment in UPK for larger counties stood at 0.66% of the population compared to 0.71% in smaller counties.

While the number of preschool options may be fewer, it did not seem to deter families from enrolling in UPK and receiving free preschool hours in more remote areas of Colorado.

“I have four invoices for $1,080 each, I’m panicking,” said Camilla, a mother of a three-year old at preschool at Monroe Elementary, a school in a predominantly Hispanic area, who asked not to use her last name for privacy reasons.

“If I do have to pay that, I have no idea how the hell I’m going to do that, that’s literally my entire income,” she said.

The state might cover 10 hours of free preschool to select three-year-olds, but funding is not guaranteed if the child does not have an IEP, and the school has not made it clear what other funding options are available to Camilla, if any.

As a parent of three kids who works full-time, Camilla chose to enroll her son in a full day anyway because she doesn’t have the option of staying home with him.

“It’s a risk I'm willing to take,” she said. “But I don’t want to tell my son ‘You can’t go to school anymore, we can't afford it,’ after he’s built such a good relationship with his teacher and friends. He loves it, he learns a lot and comes home and tells me.”

Reseach shows that early educational support has a significant impact on child development, especially for children from underprivileged backgrounds.

“It proves that the earlier we start, the better for all children. And those results have a huge return on investment,” said Cassandra Johnson, a co-founder of the National Black Child Development Institute Denver chapter, now the Black Child Development of Colorado, whose mission is about the advancement of Black children.

“That over 95% of the brain is developed by age five is really a critical piece of information to have,” Johnson said.

Alice, who asked to keep her last name anonymous for privacy reasons, identifies as biracial, having both a white and Black parent. She said she appreciates receiving some support through the state. Her three-year-old daughter, enrolled at Academia Ana Marie Sandoval within Denver Public Schools, receives a partial tuition break to attend a half-day.

At $400 a month, “it's way cheaper than daycare, we would have been paying $1600 a month if we kept her in another preschool day program,” she said.

While three-year-olds are receiving support from the state, the statute’s focus for UPK is on children "in the year preceding eligibility for kindergarten" — primarily four-year-olds — providing 15 hours a week of state-funded preschool.

By late November 2023, almost 39,000 four-year-olds were enrolled in UPK, receiving 15 hours free each week.

That’s a significant increase over the number of four-year-olds served by CPP last year when approximately 15,339 four-year-olds were enrolled in pre-school.

UPK does also provide additional support to four-year-olds beyond the required 15 free weekly hours if they meet the low-income threshold (below 270% of the Federal Poverty level) and have one qualifying factor, including having limited English proficiency in the home, experiencing homelessness or having a child in foster care, or having an IEP.

Many families and providers feel that these standards to access additional free hours are too high.

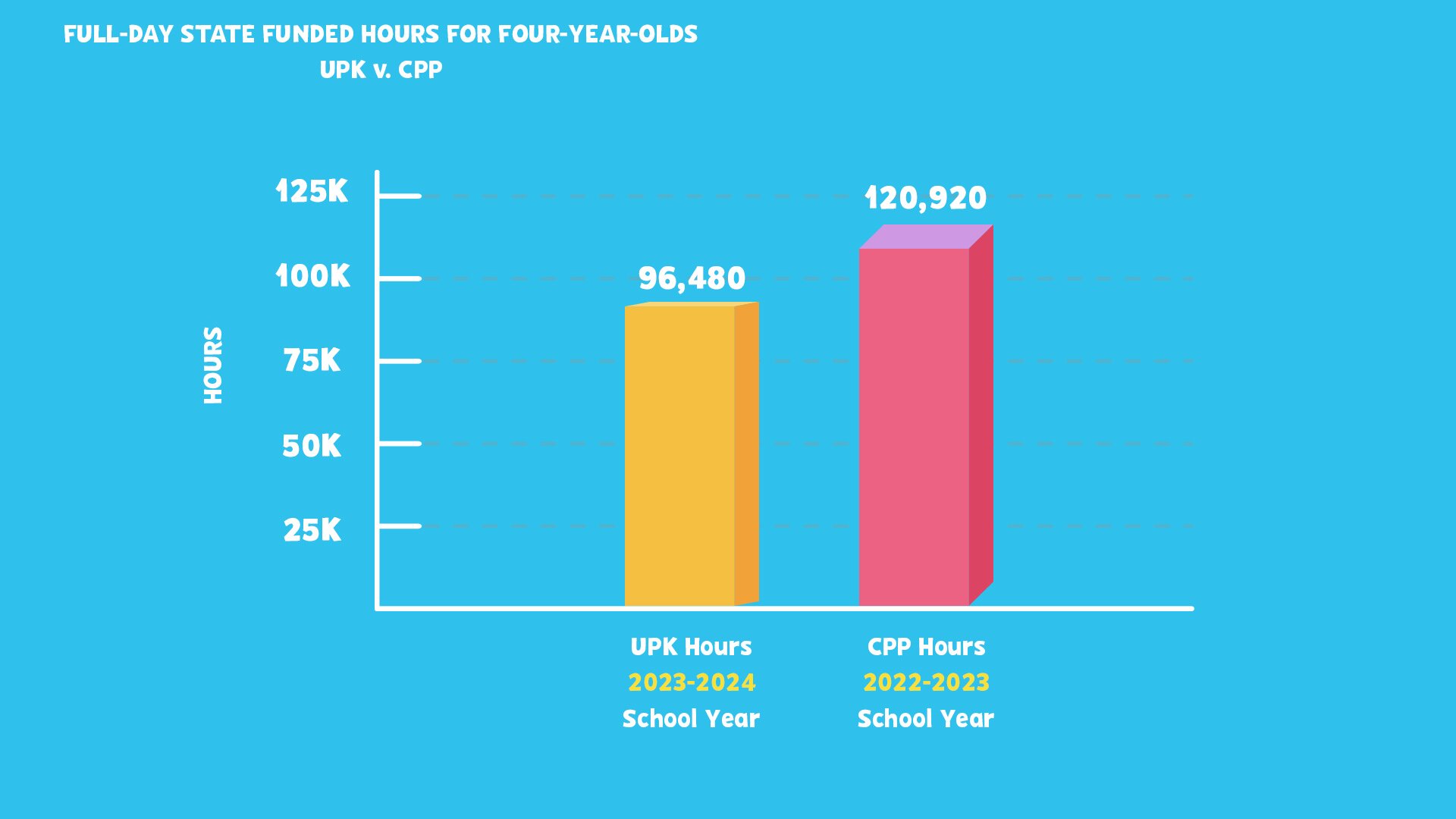

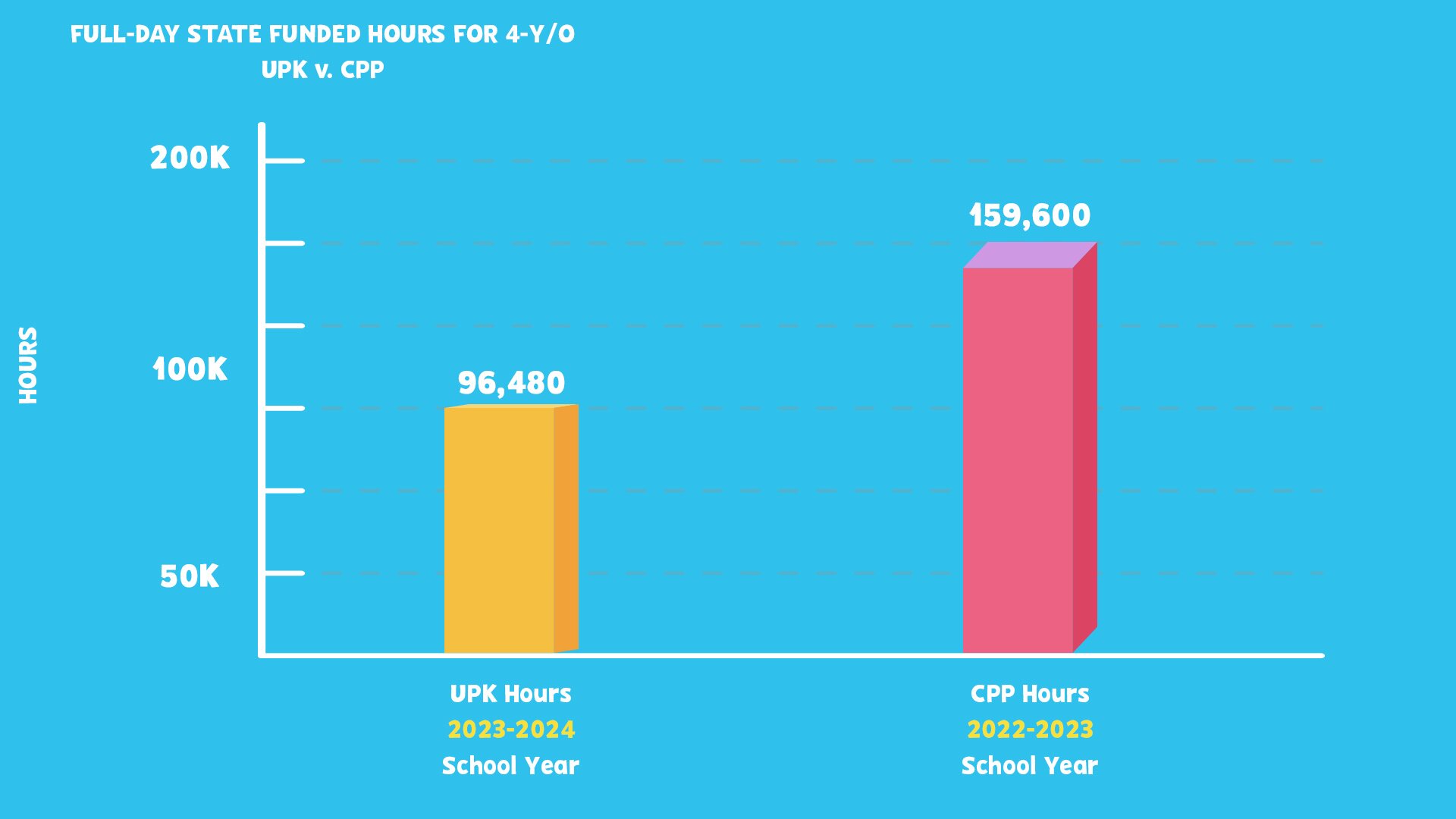

For the 2023-2024 school year that ends in May, UPK covered the cost of additional preschool hours for children who met the criteria — 30 hours total — to 3,216 four-year-olds.

While CPP capped "full-day" pre-school at 20 free hours a week, and UPK caps the same at 30 free hours a week, the previous program served 6,046 children. That's almost 40 percent more children who received a full-day program under UPK.

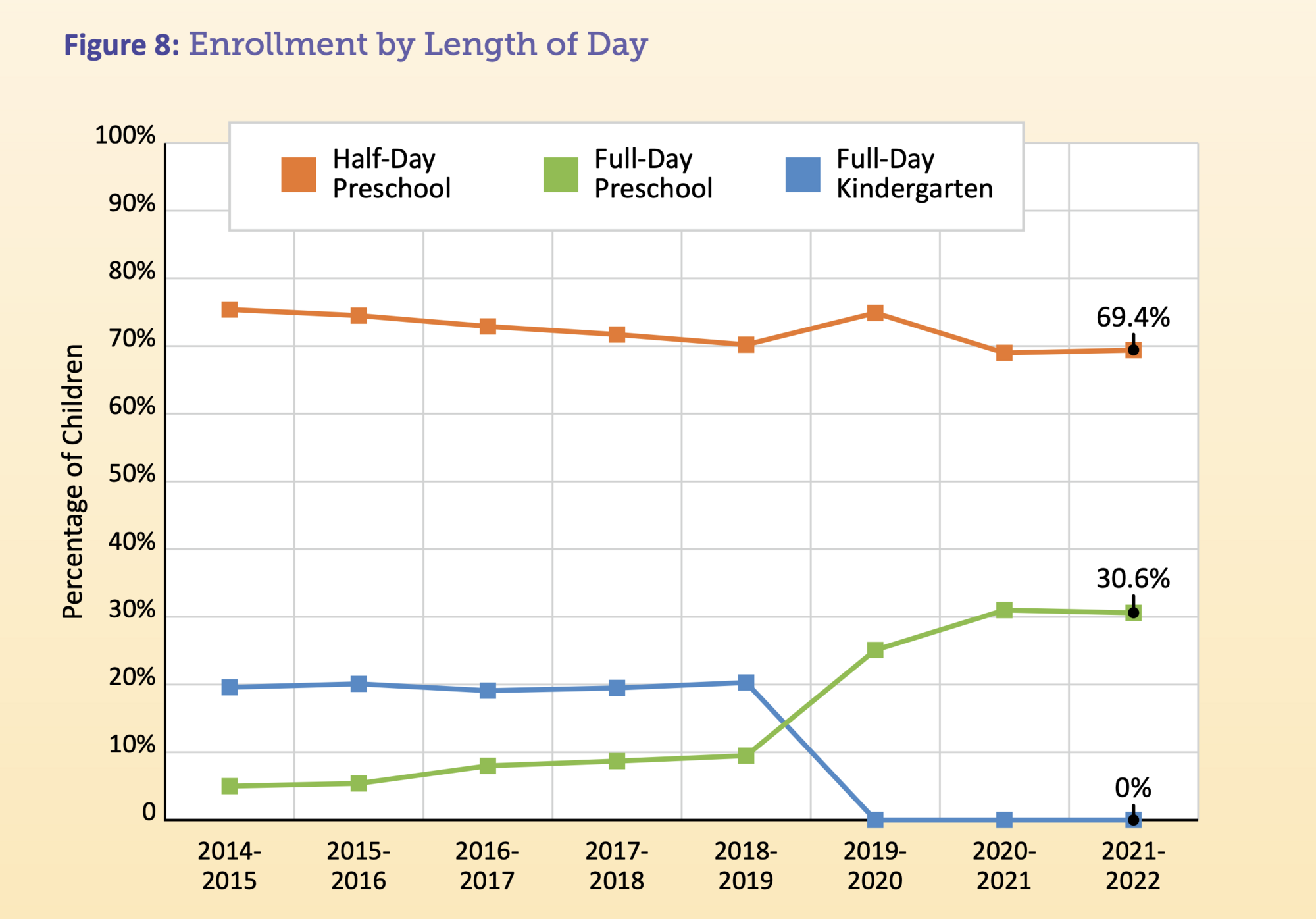

According to the 2022 CPP legislative report, enrollment into the full-day program under CPP was consistently increasing over the past five years.

“This rise in the utilization of full-day positions reiterates the importance of full-day programming options for families,” the report said.

“The full-day option benefits families and children as it increases continuity of care and access to service and instructional time for children who may benefit most from preschool experiences,” it said.

Overall, CPP provided more hours and funding for some of the state’s most vulnerable four-year-olds to attend full-day pre-K than the first year of UPK.

Ellen Emmerling is a single mom of three in Hugo — a town of 798 people in the Eastern Plains. Her five-year-old son, enrolled at the Country Living Learning Center, originally qualified for the maximum number of 30 hours through UPK.

Then she was notified by the state that she was no longer eligible for additional hours beyond the base-level 15. She currently receives about $120 monthly towards her child care bill.

“I'm grateful for it, but I was a little disappointed I didn't get the full funding because I paid just shy of $1,000 a month for daycare,” she said.

“When they changed the qualifications, one of the biggest things was bilingual. He's not bilingual. That was a huge kicker.”

Previously, she also qualified for The Colorado Child Care Assistance Program (CCCAP).

“Then they walked in and were like, nope, you make too much,” she said. “I don't get any food stamps, I don't get any rent assistance, nothing.” As a single mother of three children, Emmerling brings home $40,000 annually.

“This conversation is about equity versus equality,” said Johnson.

Launched in 1988, CPP’s mission was to serve children most in need, covering tuition for qualifying families based on family, economic, or developmental factors until the program was replaced in 2023 by UPK.

“If we’re going to use the funding for CPP towards a new universal model, then a component of that universal model needs to have some of the features that CPP did as a targeted program,” she said.

Lizzie Mulvey is the executive producer of investigative journalism at Rocky Mountain PBS. Lizziemulvey@rmpbs.org.