They faced foreclosure not from their mortgage lender, but from their HOA

This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Rocky Mountain PBS. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

This is the beginning of an ongoing reporting project about homeowners associations in Colorado. If you have experiences with a Colorado HOA, we want to hear from you.

AURORA, Colo. — In a year when it felt like everything had gone wrong, a knock at Miesha Ross’ door one December day brought more bad news.

“There was a process server who came and knocked on my door and served me with a foreclosure notice,” Ross said, “and of course I freaked out.”

Ross had already had a string of bad luck in 2017 — a car wreck and a period of unpaid maternity leave after the birth of her third child left her struggling to pay the bills. She said she worked with most of her creditors to catch up. Getting served with a foreclosure case that day caught her by surprise.

“I’m like, ‘OK, I worked something out with the mortgage company,’ and that’s who I would think would be able to foreclose,” Ross said. Instead, the notice was from her homeowners association, the group that takes care of the upkeep of her community of townhomes.

“I had no idea that an HOA could foreclose on you.”

That knock at the door marked the start of a four-year legal fight between Ross and the Timbers Homeowners Association I Inc., which governs a complex of 394 units in Aurora, southeast of Denver.

Ross, a single mother, filed for bankruptcy twice, in 2017 and 2019, to try to catch up on her debt to the Timbers and save her home. She has since paid more than $5,600 to cover the HOA’s legal fees, an expense the association is allowed to pass on to members. She has worked to keep up on her monthly HOA dues, though a few times she was late. The association’s attorney recently filed a motion to have her bankruptcy dismissed, saying she has not made timely payments. Ross is fighting back, asking a judge to declare she has paid enough.

“I can understand if I wasn’t making any payments at all and just refused to pay,” Ross said. “I’m paying, and you’re still coming after me.”

Ross’ story illustrates the enormous power that Colorado’s more than 10,000 HOAs wield over homeowners. Many HOAs require residents to make routine payments, called assessments, to cover common expenses such as landscaping, trash pickup, water and sewer services, and amenities like neighborhood pools, clubhouses and playgrounds. In townhouse and condo communities like the Timbers, where assessments are $355 per month, those payments often also cover community insurance.

Under state law, HOAs can initiate foreclosure proceedings against homeowners who owe money to them, and their actions aren’t subject to any oversight from regulatory agencies.

The state estimates that more than 2.6 million residents — nearly half of Colorado’s population — live in homes governed by a homeowners association. Those HOAs filed more than 2,400 foreclosure cases from January 2018 through February 2022, according to an analysis of state court data by Rocky Mountain PBS and ProPublica.

During that same time, the analysis shows, at least 215 cases initiated by HOAs have resulted in sheriff’s sales in which the homeowners lose possession of their property.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, state and federal governments issued moratoriums on most foreclosures by banks and mortgage lenders, prompting a significant slowdown of the proceedings nationwide. The national association of HOAs similarly recommended pausing foreclosures. But HOAs had wide discretion to make their own choices, and in Colorado, roughly 450 HOAs filed more than 730 foreclosure cases from April 2020 through July 2021.

Lindsay Smith, chair of Colorado’s legislative action committee for the Community Associations Institute, a trade organization for HOAs and their managers, said she typically advises HOAs against foreclosure except as a last resort. But she acknowledges it’s a “very effective” way of getting homeowners to pay when other collection efforts fail.

The data shows that the vast majority of Colorado’s HOAs have not taken the extraordinary step of foreclosing against homeowners at all in the past four years. But there are pockets where associations are turning to the so-called last resort of foreclosure again and again.

One such pocket is Green Valley Ranch, one of Denver’s largest HOA communities, with more than 4,000 units.

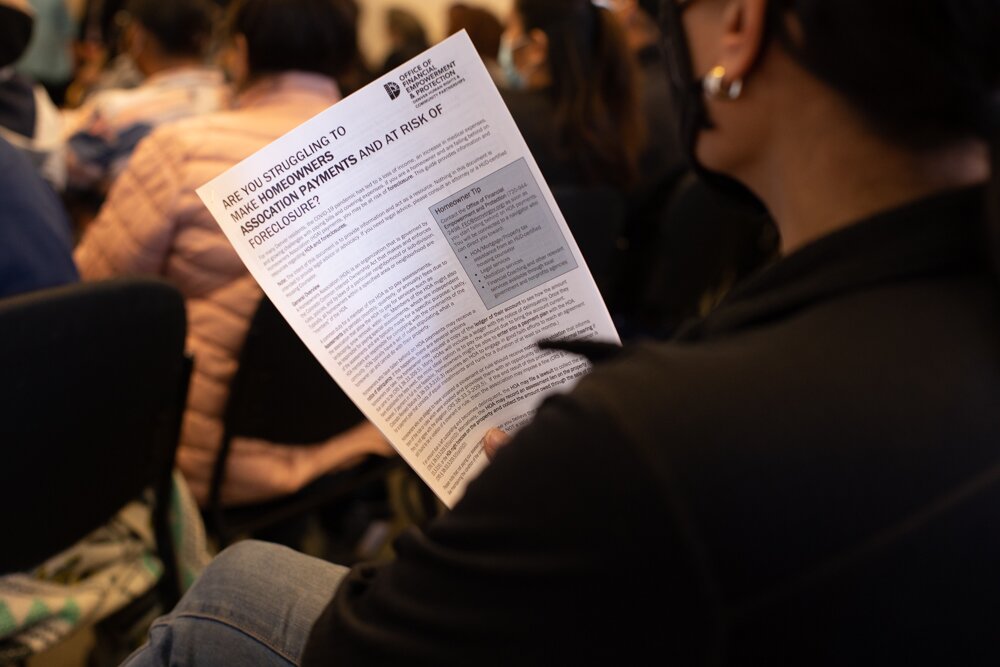

Town hall meetings, protests and petition drives sprung up in recent weeks after residents learned that dozens of homeowners there have faced foreclosure since 2021. Court data shows that the Master Homeowners Association for Green Valley Ranch has filed 79 cases since 2018.

The office of Colorado Gov. Jared Polis has called the foreclosures at Green Valley Ranch a sign of the “far reaching, unchecked powers” of HOAs in the state, and he has said he supports ongoing legislative efforts at the Colorado Capitol to limit those powers.

A tenth the size of Green Valley Ranch is the Timbers, an HOA that has filed 41 foreclosure cases against 31 homeowners since 2018.

The Timbers HOA’s board of directors and its property manager told Rocky Mountain PBS and ProPublica that the association’s collections practices have helped reduce by two-thirds a $200,000 shortfall in membership dues as of 2017, and the community has been able to complete a mounting list of repairs and maintenance that had long been delayed.

But the board and property manager declined to discuss the details of the foreclosure cases the Timbers has filed in public court.

“Stories like the one you are pursuing are always one sided. From social media to the actual local news media, HOAs, management companies, boards, and managers are demonized,” said Craig Miller, a representative from the HOA’s property manager, The Colorado Property Management Specialists, in an email. He said he would “happily provide details” if owners signed a consent form witnessed by a notary public.

Ross did just that. Three days later, the property manager again declined to give details, asking for even more paperwork.

In a statement, the board said it generally works with homeowners who fall behind on their bills to avoid legal action.

“The Timbers would rather work with and communicate with its members to resolve delinquency issues than rely on legal action. Over the years we have implemented payment plans and other tools that allow a member to regain their good standing,” the board wrote. “Unfortunately, not all our members with outstanding obligations are willing to work with us to utilize these options, which can result in legal action being taken.”

"They Can Take Away Your Home"

When people purchase houses in an HOA, they sign documents that bind them to obey the association’s covenants — and to pay fines, and possibly even collection costs, if they don’t.

“They don’t understand that they’re giving up, in essence, control of their property to a separate entity, the association. And if people don’t understand that from the very beginning, then bad things can happen,” said Jose Vasquez, a supervising attorney who represents low-income clients involved in housing disputes for Colorado Legal Services.

Some HOAs are responsible for expenses like street paving and lighting that might otherwise fall to local governments, and Smith said HOAs can’t pay for that kind of work if homeowners are not keeping up.

“We need to be able to provide the services that we are required to provide, and that means that we have to collect,” Smith said. “And sometimes that’s not as pretty as you might hope.”

The Timbers HOA’s board and its property manager pointed to the 2021 collapse of the Champlain Towers South condominiums in Surfside, Florida. Later reports said the condo association had not set aside enough funding to complete urgent structural repairs, and the association was in the process of billing homeowners to pay for the work when the tower collapsed. The HOA industry at large looks at the Surfside disaster as an example of what can happen when there is not enough funding coming in from an association’s members to fix what is broken.

“Some associations have no choice but to stop funding maintenance, repair, replacement, and/or reserves. Over time, this can lead to delayed maintenance and deterioration of the buildings, landscaping, and other elements in the community along with the property values of such homes,” the board and property manager said in a statement.

When residents don’t pay, HOAs can file liens against their property. And Colorado law allows HOAs to seek foreclosure on their liens when residents are at the equivalent of six months behind on their routine assessments. That total may encompass more than the assessments themselves — it can include late fees, interest and legal fees, and fines for other violations, such as dead grass or faded exterior paint.

When a foreclosure order is granted by a judge, the local sheriff’s office sells the property to the highest bidder. The minimum price is set by the HOA, based on what the association and its attorney say they are owed, and the HOA also places a bid for that amount. This means the HOA itself can win the auction and purchase the property, potentially allowing the association to sell or rent the unit to turn a profit. Sheriff’s sale records show HOAs statewide have purchased at least 36 properties at foreclosure auctions since 2018.

At most of those auctions, homes were sold at far below fair market value. (Sheriff’s sales don’t extinguish any mortgage that may be owed, so the original homeowner may still owe a mortgage unless the new buyer pays it off or the lender proceeds with its own foreclosure action.)

Traditional foreclosures, handled by public trustees and typically brought by mortgage companies when homeowners fall behind on their payments, are far more common than HOA cases. More than 13,000 traditional foreclosure cases were filed between 2018 and early 2021 in Colorado. But the debts in those cases are often far larger.

Colorado does not regulate HOAs, and little has been known about how often the groups litigate against homeowners. The local industry organization said it does not keep track of how many foreclosures HOAs initiate in Colorado.

The state’s quarterly foreclosure reports — which are no longer being created due to state budget cuts during the pandemic — do not include HOA foreclosure numbers at all. A state office created to inform consumers and lawmakers about HOAs confirmed that it does not track the numbers either.

Several Timbers homeowners said they kept up with their mortgage but still faced losing their homes because they fell behind on their monthly dues.

“At first it was denial, like, ‘Oh, that’s just a threat. They can’t take away your home.’ And then, as things progressed, [we realized], ‘Yes, they can take away your home,’” said Timbers resident Mary Kunic.

Kunic and her husband were served with a foreclosure lawsuit from the HOA in 2018, 12 years after she purchased their townhouse. Kunic doesn’t know many of the details of what happened because she said her husband, who died in 2020, handled the situation. But she said he had to borrow roughly $10,000 to pay off the HOA and keep their house.

Kunic, 49, said she didn’t know until she was contacted by Rocky Mountain PBS and ProPublica that her home came within three days of being auctioned off at a sheriff’s sale. She also didn’t realize how much of the payment her husband made had gone to paying the HOA’s legal fees.

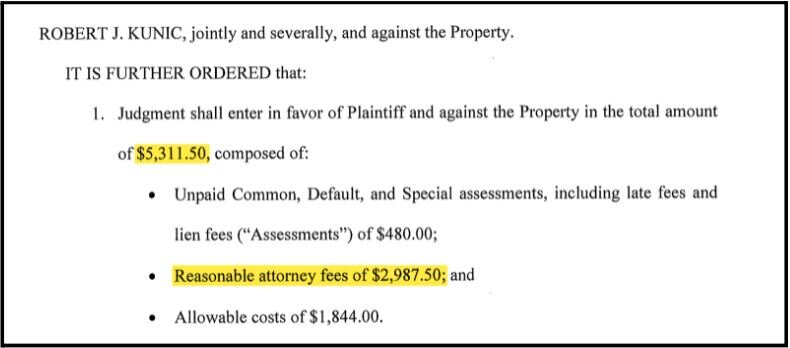

Court documents show the Timbers obtained a default judgment for foreclosure of the Kunics’ home in the amount of $5,311.50, but only $480 of that total was actually owed for assessments, late fees and lien fees. The remainder represented legal costs of more than $1,800 and attorney’s fees of nearly $3,000, payable to the HOA’s collections attorney, Tammy Alcock. After the sheriff’s sale was scheduled, Alcock added another $1,920 in post-judgment attorney fees to the total.

Of the $5,311.50 default judgment that the Timbers won against the Kunics, only $480 was for assessments, late fees and lien fees. Alcock Law Group, the HOA’s attorney, was owed $2,987.50 of the total. (Obtained by Rocky Mountain PBS and ProPublica)

Vasquez, who has not represented any of the Timbers homeowners interviewed for this story, said it is common for homeowners facing HOA foreclosure to see large legal fees added to their bills.

“In many homeowners association cases I’ve seen … the bulk of the amount that the association is trying to collect is attorney’s fees,” Vasquez said. “If you have a situation where you have all these additional fees that they’re now being charged, it makes it much more difficult for the homeowner to preserve their home.”

Although Kunic gave the Timbers written consent to answer questions about the legal fees applied in her foreclosure case, the HOA said it could not comment unless she could prove that she was the court-appointed personal representative of her late husband’s estate.

“I could attend the next HOA meeting with his urn of ashes and ask them to talk to him themselves,” Kunic said.

In general, the Timbers said it cannot pay its bills if homeowners are not keeping up on theirs, and that allowing some people to fall behind is “unfair” to those who pay on time. And Kunic said she understands the HOA’s perspective.

Although her foreclosure case was closed years ago, she still worries about keeping her home. She works long hours as a nurse, but she fears she may not be able to keep up with the increasing HOA dues and other expenses without her husband.

“They have said a couple times at HOA meetings that, if people don’t like certain parts about the structure, they can move,” Kunic said. “Where could I afford to go?”

"It Scares Me That They Can Have So Much Power"

A key box hangs from the front door of a corner unit at the Timbers, next to a broken doorbell camera. A gap in the blinds shows the inside is empty.

The previous owner, John Saffer, moved out hastily last fall after his townhouse was sold at auction to a real estate investor for $15,282.

Saffer said he lost his job in 2019 and filed for bankruptcy to avoid foreclosure from his mortgage lender. After his bankruptcy case was closed, the HOA filed to foreclose, and Saffer said he did not have the funds to fight it.

“When buying a house, it seems all of them have some kind of HOA, and it scares me that they can have so much power,” Saffer said.

“I sunk $15,000 to $20,000 into a house,” and instead of building equity, he said, he “got nothing back from it.”

Saffer’s property is one of three Timbers properties sold at sheriff’s sales since the start of the pandemic, during a period when the HOA has been funding repairs to the common areas of its property.

The units at the Timbers were built in the 1970s. The complex covers 55 acres of the sprawling suburb of Aurora.

Over the years, the community has needed repairs but did not always have enough funds to do the work.

“The Timbers had mounting capital maintenance obligations, such as the replacement of 40-year-old water lines that were routinely bursting at great expense and inconvenience to our members, 40-year-old asphalt which was rapidly turning our parking lots into gravel, necessary roof replacements, and significant repairs [needed] to one of the association’s swimming pools which made it unusable,” the board said in a statement.

Eventually, the community voted to take out a $3 million line of credit to try to complete necessary repairs and maintenance.

The community had gone without a dedicated property manager for 13 months before it hired The Colorado Property Management Specialists in 2017. That same year, the HOA transitioned to a new collections attorney: Alcock Law Group.

The board said in a statement that, before 2017, the HOA shared the cost of collections with a law firm, leading to shortfalls that continued to grow because “the collections company was not sufficiently motivated to find and collect outstanding amounts.”

In contrast, Alcock’s website says, “Our goal is to provide aggressive representation to bring the rate of delinquent assessments down by striving to collect not only the delinquent assessments but also all attorney fees and costs incurred by the Association quickly and efficiently.”

Records show close ties between The Colorado Property Management Specialists and Alcock.

The property management firm works with 26 communities, according to its website, and court records show Alcock has represented 15 of them in foreclosure litigations. Fourteen such cases, including the action against Ross, were filed on behalf of the Timbers in the final months of 2017, after Alcock was hired. By comparison, records show the HOA had filed just one foreclosure case in all of 2016. The Timbers board confirmed it hired Alcock on the advice of The Colorado Property Management Specialists.

Alcock declined an interview. Instead, she said in an email, “I take direction from the Association’s Board through its property manager pertaining to the commencement of lawsuits for judicial foreclosure and matters regarding settlement.”

The HOA’s collections efforts continued through the pandemic, despite the recommendation by the Community Associations Institute that associations adopt a moratorium on foreclosures through July 2021 and “waive late fees and penalties for owners who face temporary financial hardships due to COVID-19.”

The Timbers said it adopted a temporary COVID-19 resolution that “offered extended payment plans to any homeowner who requested assistance due to COVID.”

But that resolution did not stop the HOA from seeking to foreclose. Court records analyzed by Rocky Mountain PBS and ProPublica show the Timbers filed 17 foreclosure cases from April 2020 through July 2021. Only two much larger associations sought to foreclose more often during the same period. The Timbers filed another three cases in January.

The Timbers’ 394 units are governed by a homeowners association. (Jeremy Moore/Rock Mountain PBS)

Unlike banks and mortgage lenders, HOAs have had wide discretion to foreclose on homeowners during the pandemic. (Jeremy Moore/Rocky Mountain PBS)

"Our HOA Is Broken"

One day in December, Edward James sat at his computer in the cramped home office in his Timbers townhouse.

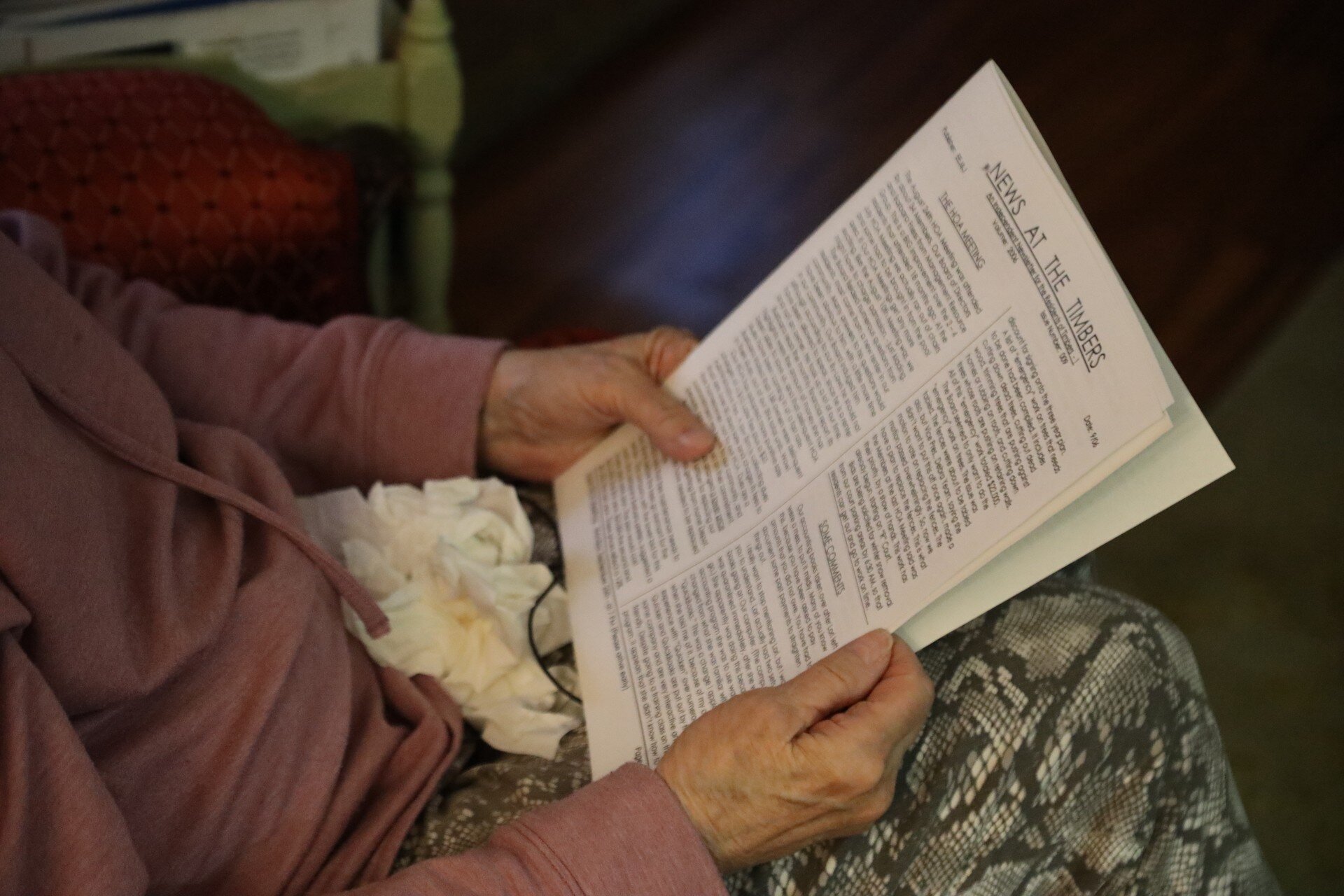

“News at the Timbers,” James titled his document, as he had for years when he wrote an independent newsletter for the community. Beneath it, he typed the words, large, bold and underlined: “OUR HOA IS BROKEN.”

James would never finish his newsletter or share it with his neighbors. He died of COVID-19 a few weeks later at the age of 73. But he left behind a collection of records showing how he and his wife nearly lost their home, purchased more than 30 years ago, in a dispute over payment due dates during the pandemic.

James’ widow, Janet, lamented how much time he spent at the end of his life fighting with the HOA.

“He got so stressed and he wanted to move away from here. And I told him, ‘I can’t,’” Janet James said. “It was a miserable couple of years for both of us. Him, because he wanted out. Me, because he was so upset and so stressed.”

That stress began with a disagreement over $25 late fees.

The Timbers’ collection policy states that payments are due on the first day of the month, and those not paid within 30 days are subject to late fees. Month after month, Edward James paid online through the HOA’s website and saved his receipts showing he paid within 30 days.

Janet James said her husband studied the HOA’s rules and argued when he did not feel they were being followed. (Alexis Kikoen/Rocky Mountain PBS)

Yet The Colorado Property Management Specialists assessed late fees on the James account in each of those months, telling him that the payments were posted on the date it received them rather than the date James submitted his payment. Records show the company waived several late fees for James and then told him that, if he wanted to avoid further fees, he needed to pay earlier in the month.

James continued paying the full amount of his monthly assessments but did not pay the late fees or additional $10 processing fees being added to his account. When he argued against the fees, the company accused him of harassing behavior and sent him letters warning that he would be fined for failing to treat the board and its vendors with “respect, courtesy and dignity.”

Because he was not paying off his balance, the late fees continued to accumulate monthly, and eventually the HOA placed a lien on the property and turned his account over to Alcock.

“My husband was very stubborn. … He wasn’t going to pay it, even though it was very minor,” Janet James said. “He felt like [if] he did the right thing, it would all be OK. And it wasn’t OK.”

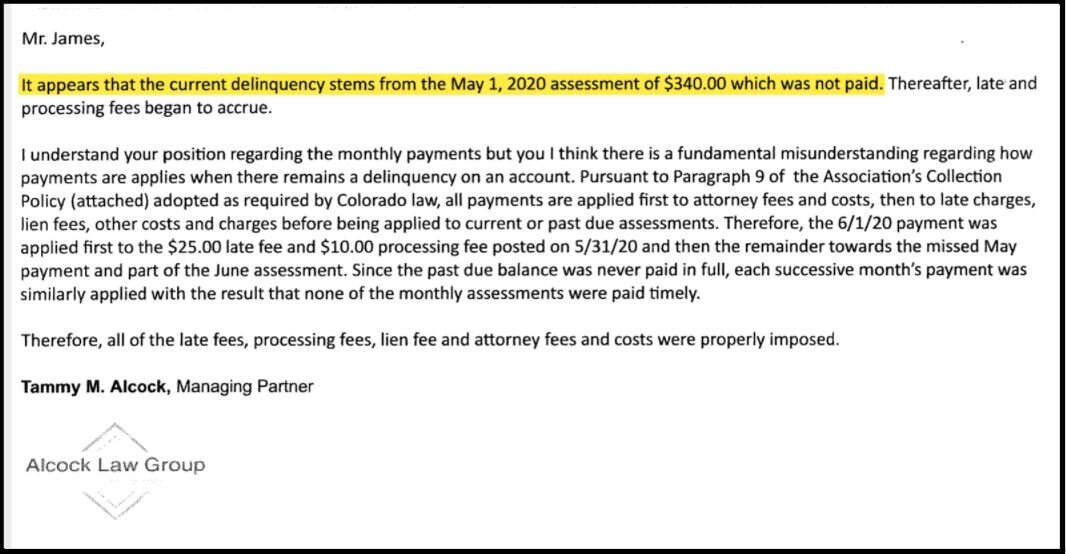

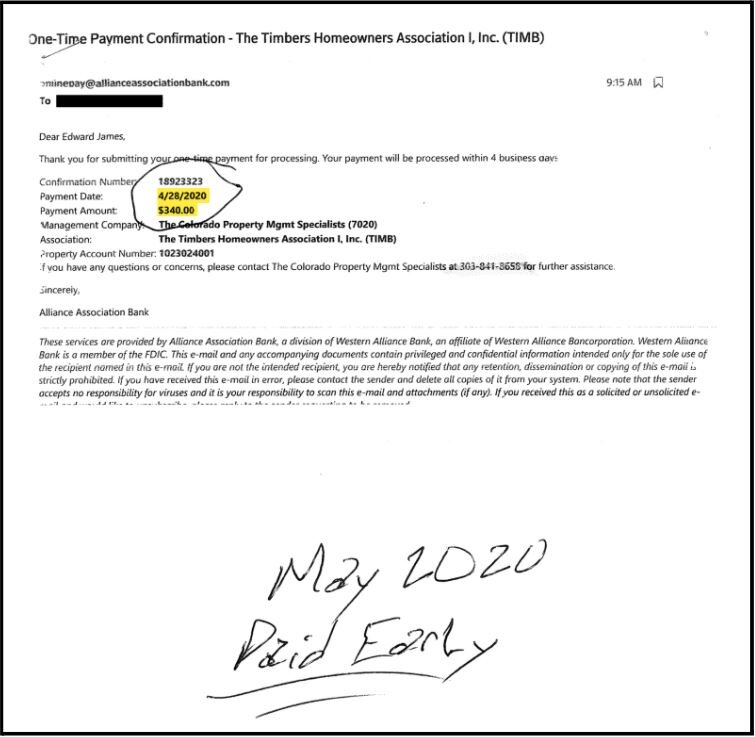

Records obtained by Rocky Mountain PBS and ProPublica show James emailed his receipts to Alcock, writing, “From these documents I hope you can tell CPMS they have no case.” Alcock responded, telling James his delinquency stemmed from missing his May 2020 assessment. He then emailed her a receipt showing he had in fact made that payment early. Two months later, in February 2021, she filed a foreclosure case on behalf of the Timbers.

In an email, Alcock explained to Edward James that his delinquency stemmed from missing his May 2020 assessment. He responded with a receipt bearing a handwritten note and showing he had in fact made that payment early. Two months later, Alcock filed to foreclose on the James house on behalf of the Timbers. (Obtained by Rocky Mountain PBS and ProPublica)

Upon being served the lawsuit, James emailed Alcock several times making settlement offers. But he did not respond in court, which allowed the HOA to secure a default judgment for foreclosure and schedule a sheriff’s sale of the James home.

Janet James said she and her husband borrowed money from a relative to pay off the total owed and avoid the foreclosure sale, signing a settlement agreement in which the couple agreed to pay more than $7,700 — an agreement that specifically stated that “the amount of attorney fees and costs charged in this matter are reasonable.”

That final amount included more than $7,000 in legal fees and costs billed by Alcock Law Group. The couple’s account ledger shows that all they owed the HOA at the time they reached the settlement was $725 — a total that Edward James continued to dispute.

Even after signing the agreement, James sent a letter to the HOA’s board demanding the Timbers, The Colorado Property Management Specialists and Alcock repay all of the expenses the Jameses incurred in their effort to avoid foreclosure.

Alcock responded with a letter of her own.

“These comments demonstrate a clear and deliberate effort to damage my business and my professional reputation. I expect an immediate retraction and apology without which I will consider legal action of my own,” Alcock wrote.

In a final act of defeat, James emailed Alcock an apology.

It’s clear, between his newsletter that often criticized the community’s leadership and his protests over late fees, that Edward James and the HOA had a contentious relationship.

Janet James provided the HOA with written consent to answer questions about her case, but the Timbers said it could not comment because she had not signed the liability form it had written or provided a separate authorization from her late husband’s personal representative.

In an email, Alcock also said she could not respond to detailed questions about James and other homeowners since “most of your questions would require that I violate the attorney client privilege regarding communications with my client or would violate my obligations under state and/or federal law — neither of which I will do.”

Janet James said she bears no ill will toward the Timbers HOA’s board or its property managers. Instead, she wants a change in state law to give homeowners more of a chance to prevail in these kinds of disputes. She said there’s a sad lesson in her late husband’s fight against the HOA.

“You can’t win,” she said. “Save your house and pay [the fees], or get the law changed.”

“My Mom Didn’t Buy That House 40 Years Ago to Have It taken Right Out From Underneath Her”

Not even death can stop a foreclosure proceeding.

Jayne Wilson was one of the first group of Timbers homeowners when she moved to the community in 1978.

“She liked it,” said Betsy Wilson, Jayne’s daughter. “It had a pool — which in Colorado, it’s not the norm — and the tennis court, and the basketball court. She loved to host people, all of us over there on her back porch.”

Wilson stayed in her townhouse until 2020, when her health began to suffer and her memory started to decline. She moved in with her daughter, who said she took over paying her mother’s bills but did not notice that the HOA payments were no longer automatically coming out of Jayne’s account.

Jayne Wilson died in April 2021, on her 86th birthday. A few months later, Betsy said she found some mail indicating her mother’s home was scheduled to be sold at a foreclosure auction.

“I had no idea that it was going on,” Betsy said.

The Timbers declined to answer questions about Jayne Wilson’s case without a liability waiver, and Betsy Wilson was unavailable to sign the form.

But court records show Jayne Wilson was never served in person with the foreclosure papers from the Timbers. A process server wasn’t able to find her, so the court allowed the HOA to publish the notification of the foreclosure case in the local newspaper instead. Other notifications about the court process sent to her in the mail were returned undelivered.

Wilson’s family had to pay more than $17,000 to stop the auction, including more than $5,600 in legal fees.

“I realize that they hadn’t been paid, but it was a mistake, and she had paid it all those years faithfully,” Betsy said. “I’m certain that my mom didn’t buy that house 40 years ago to have it taken right out from underneath her.”

“Isolation and Shame Don’t Solve Problems”

In a committee room at Colorado’s state Capitol in early March, lawmakers heard stories from homeowners asking the state to place limits on the fines, late fees and legal fees that can cause a small HOA debt to snowball into one so large that it costs someone their home.

“Taking someone’s home away should be the last resort,” said Rep. Naquetta Ricks, an Aurora Democrat. “The practice persists because attorneys are paid from the proceeds of selling the house, further reducing homeowners’ equity. These predatory practices must be stopped.”

Ricks is sponsoring a proposal aimed at removing an HOA’s ability to foreclose for nonpayment of fines and fees from covenant violations like grease stains in driveways and unmowed grass.

But some HOA representatives and members of the Community Associations Institute told lawmakers that the proposed limits would simply increase costs for homeowners. The legislation is being amended by its sponsors and is currently set for a committee vote next week.

Andrew Mowery, an HOA homeowner advocate and blogger who is part of a group of homeowners from across the state who helped shape the legislation, said stories like those at the Timbers illustrate a need for reform.

“We are not just doing this for a few anecdotal stories from some malcontents. This is something affecting a large number of people. The sunshine of the day needs to shine down on this and expose this,” Mowery said.

Some of the Timbers homeowners who have faced foreclosure said they only recently learned that so many of their neighbors have also been sued by the HOA.

Kunic said she decided to share her story because she wants to help. She said she’s hoping to join with neighbors to start a community food pantry to help ease some of the burdens that many in the community seem to share.

“Isolation and shame don’t solve problems. And I want to help be part of the solution so that other people don’t end up three days away from losing their home,” Kunic said.

About the Data: How We Compiled Information on Sheriff’s Sales and HOA-Initiated Foreclosures

Rocky Mountain PBS and ProPublica’s analysis of sheriff’s sale data was compiled by collecting documents kept by sheriff’s offices and county clerks around the state and by reviewing sheriff’s sale documents filed in court.

The news organizations’ analysis of foreclosure cases brought by HOAs depended on a database of over 2,400 such cases filed between Jan. 1, 2018, and Feb. 28, 2022. To build this list, we first obtained, via a public records request to the Colorado state court administrator’s office, a list of all foreclosure cases that were categorized by the state as “Other than rule 120 (FC)” or R5. These are two categories for judicial foreclosure cases, which are not initiated by mortgage lenders. We then scraped additional information on those cases from the Colorado Courts Public Access Terminal. Because we found inconsistencies and misspellings in the court records, we used a combination of the OpenRefine tool and manual labor to clean the data by combining multiple versions of the same plaintiff name and removing spelling errors. We then used keywords to identify court cases relating to HOAs. We used a public records request to the Department of Regulatory Agencies to obtain data on HOAs’ registrations with the state. In an effort to concentrate on residential properties rather than shared vacation homes, we excluded cases involving HOAs that have indicated that their communities include timeshare units.

Brittany Freeman was the executive producer of investigative journalism at Rocky Mountain PBS.

Photos and videos by Rocky Mountain PBS staff.