Athletes have long pushed past mental health issues, but the conversation is starting to change

AURORA, Colo. — When Simone Biles shocked the planet at the Tokyo Olympics last month to focus on her own mental health, Kathryn Ames had to smile.

She certainly didn’t revel in the internal struggles voiced by one of America’s all-time athletic heroes, rather Ames was glad that Biles had brought something else from the fringes into the larger spotlight that always follows her — the need for athletes to draw a line at their own personal needs.

Winning another all-around gold medal and leading the U.S. to a team gold would have further cemented the athletic legacy of Biles (aka the Goat, Greatest of All Time) but her refusal to sacrifice her mental and physical health to do it as athletes so often do can have a much greater impact.

It was an admission that was extremely important in the minds of many including Ames, a counselor at Aurora’s Regis Jesuit High School who spends many of the rest of her waking hours helping athletes in high school and college with mental health.

“I hate to see anyone suffer, I’m just so proud of Simone Biles to take that platform to take care of herself and put herself first,” Ames said. “I know there were so many different opinions and reactions, but for her to model that for young people and to hear other people come forward is great. But the way I receive it is that we are failing as a system and that we need to do better.

“Going through the isolation of the pandemic and a lack of connection has brought all these things to the surface.”

Mental health is composed of a wide spectrum of issues, but things recently trended towards the darker end, especially for young people, to the consternation of healthcare professionals.

Aurora’s own Children’s Hospital Colorado declared a state of emergency in regards to pediatric mental health as Colorado state date continues to show more than 100 children between the ages of 10-19 have committed suicide each year since 2017, while many more attempts have been unsuccessful and thoughts are on the rise.

“If we don’t talk about mental health, that’s when people tend to feel more isolated or when they feel they are the only ones feeling a certain way,” Ames said. “Just because you are anxious one day, that doesn’t mean you are diagnosed with anxiety and just because you have sadness doesn’t mean you are depressed. It’s ‘how do we work through these things?’”

Finding a perfect way to reach and help young people is extremely difficult, but Ames and others believe that connecting with those involved with sports — those used to training and taking coaching already — can make a big difference towards impacting society as a whole.

Biles uses the biggest stage

Jordyn Poulter was in Tokyo with the U.S. women’s volleyball team when the news came out about Biles, the 24-year-old overwhelming favorite for an all-around gold medal.

Biles pulled herself out of the team competition and later posted on social media that she “felt the weight of the world on my shoulders.”

The Olympics, the largest stage in sport and the dream of millions, bring an extra level of pressure that requires immense amounts of self-sacrifice. For Biles, it finally became too much in the moment.

It floored Poulter — former Eaglecrest High School star setter — and her teammates just like it did others around the globe, but they could all relate in some ways.

“The same as for everybody at home, it came out of nowhere that Simone stepped down and pulled out of her events,” Poulter said. “As a team, we talked about it and we couldn’t imagine just what she felt and what she was going through. I only know the pressures that I have faced in my career and it’s definitely different for someone like her who is such a focus of Team USA and the media.

“But it’s no secret that it takes a lot to compete at the Olympic level.”

Poulter didn’t envy the fact that Biles basically had the outside pressure solely on her given that gymnastics is effectively an individual sport and that nobody else on the U.S. team — talented as they may have been — had any widespread name recognition prior to the Olympics.

The fact that five other players shared the court with her on each and every point helped Poulter withstand the pressure-filled moments as she helped the Americans to their first-ever gold medal in women’s indoor volleyball.

“In a team sport like volleyball, you can lean into other people to help lift you up,” Poulter said. “In moments when you are competing in front of millions of people, it’s nice to know you are not alone. You look at those five other people on the court and feel assured that you are never alone.

“It’s really special to have those other people that can help take some of the burden off.”

Another former Aurora prep star could relate to Biles in many ways given her time in an intense individual spotlight and the toll it can take.

In the early 2010s, Regis Jesuit graduate Missy Franklin took the swimming world by storm with a variety of epic feats in international competition which she accomplished as a teenager.

A four-time gold medalist at the London Olympics in 2012 while still in high school, Franklin had Biles-like stature in the world of sport.

But by the time the next Olympic Games arrived — 2016 in Rio de Janeiro — Franklin had been worn down both physically and mentally. Though her trademark easy smile and sweetness never faded, she struggled internally and she couldn’t live up to the immense standards she had set for herself.

Franklin still came home with a gold medal, but knew something wasn’t right. She battled anxiety and depression and since has been candid about dealing with them.

“You’re supposed to be really strong, you’re supposed to be really confident, and I think people sometimes forget that we’re human too,” Franklin told CNN in an interview afterwards.

Michael Phelps, professional tennis star Naomi Osaka and a variety of others came out before and after Biles with their own admissions of needing help and being in a place where they could ask for it.

But perhaps they wouldn’t have to if it had been easier to work on maintaining their mental health from a younger age.

Another kind of coaching

Kathryn Ames considered going to law school, but her work with at-risk youth that brought her to Colorado in the late 1990s when she was in her early 20s pushed her towards the mental health field.

In the decades that have followed, she has become a mother (to three children now all in their teens), a very successful lacrosse coach, school counselor and a licensed therapist. A cancer diagnosis a year ago — which she has fought successfully — gave her added perspective on the fragility of life and what kind of impact she wanted to make.

So she started her own business — Thru The Game — to support the mental health of Colorado athletes on a team and individual level. Ames recently stepped down from her job as head coach of Regis Jesuit’s girls lacrosse team — a job she loved and through which she got to coach her now-graduated daughter, Bella — but it was a sacrifice she felt had to be made.

“I really feel called to this, there is so much growth potential and it could blossom in a wonderful way,” said Ames, who finds precious time on her nights and weekends to work with a variety of teams across the Front Range in afternoon or weekend hours, mostly via Zoom calls.

Sports is something she knows well as a multi-sport athlete in high school and a longtime club and high school coach, and she feels like it has a lot of advantages.

There is already a built-in structure, plus coaches and support staff interact the athletes on a daily basis for long stretches of time, even in the offseason, which can help them detect if anything is wrong.

“I think that for so many kids, sports is where they feel their best; they grow and feel love and they are happy,” Ames said. “The flip side is that sometimes it can be worse. Sometimes they can feel alone — even in a team setting — and they carry that struggle even as they put on a face that doesn’t let you know they are suffering.

“I’ve been a coach for years and I know I’ve missed some things in my athletes and I’m a professional counselor. Can we get better at checking in with our kids and care for their whole person, not just their stats or what the goals of the team are? Obviously every team wants to win a state championship and I get that and support that, but there are other goals, too.”

In the same vein as what Ames is doing, Matt Kitashima — a local educator and longtime baseball coach, who held the head job at Eaglecrest and has also been an assistant at Smoky Hill — works with teams and individuals on his own time as a mental consultant.

Kitashima, who minored in psychology at Hastings College where he was a multi-sport athlete, works primarily with mental training in terms of sports performance and developing mental toughness in competition.

But like Ames, he sees athletics as just an avenue to a broader conversation about the overall mental health in an age group that already has so much more to deal with in everyday life — including the massive effect of social media — that previous generations didn’t have.

Kitashima also believes Biles’ admission on a worldwide stage with so many young kids that look up to her can have a far-reaching positive effect.

“Maybe if even one kid saw what Simone Biles did and it maybe gives them enough courage to go tell their parent or coach or teacher that they may need help, it was a great thing,” Kitashima said.

As longtime coaches, Ames and Kitashima fully understand the already significant demands that coaches have simply to organize, train and try to get their teams competitive.

Still, they believe it would be huge if addressing the mental health of their athletes was commonplace, much like the training they receive to deal with concussions and athletic health.

The Colorado High School Activities Association took a step toward that in 2019 when its Board of Directors approved a requirement for all prep coaches to take a course on student mental health, either through an online course offered by the National Federation of High School Associations (NFHS) or through something offered through their school district.

Coaches in the Thompson School District in northern Colorado — which has 15,000 students and includes Berthoud, Loveland, Mountain View and Thompson Valley high schools — recently got to do that during a professional development day at Mountain View, which included a presentation from Dr. Greg Dale, Director of Sports Psychology and Leadership at Duke University.

“Especially coming out of the pandemic, the mental health of our students is so important,” said Thompson District Athletic Director Kevin Clark, who organized the event.

“The calls to Safe2Tell (Colorado’s anonymous line to report concerns about individuals) have indicated there are more suicide attempts and more conversations about it,” he added. “It’s such a tough time to be a teenager, so anything we can do in our professional roles to help prepare them to have those conversations, the better.”

Clark said that more than 150 coaches from his district — including some from surrounding Windsor as well — attended the voluntary event that also included CPR certification and concussion training.

What help can do for an athlete

Aliyah Weant loved to play lacrosse and she was quite good at it, enough to become the only freshman to earn a spot on the varsity team at Columbine High School a few years ago.

Admittedly never a real social butterfly or someone who had more than a small circle of close friends, Weant suddenly went into her sophomore year without the most important person in her life, her best friend Matt, who committed suicide unexpectedly.

The two had met in middle school and grown very close before they got to high school. The relationship was turning into romantic interest as well, but then all of a sudden, Matt was out of her life.

“I had no idea, I FaceTimed him the night before it happened, like we did a lot of times,” Weant said. “I knew he struggled with things, but I think it was an impulse thing.”

Weant didn’t fully realize it at the time, but her play on the field — already filled with some pressure because she was surrounded by upperclassmen — began to suffer, her grades slipped and she began to pull away from connection with others in many different ways.

She continued to use a concussion she suffered on the field as an excuse, even after she had been medically cleared.

A close friend as well as a lacrosse coach who gave her a ride home both felt they needed to let Weant know she didn’t seem like herself. When she was confronted, she knew it was the truth.

“It sank in right away; I was scared for sure and I didn’t really know what to do,” Weant said. “I was scared to go to my parents — not because of anything that they had done and I knew they would handle it well — but the recognition and realization that I needed help.”

Weant wouldn’t make the call herself, but wrote a note to her parents asking them to get help. They reached out to Ames, who Weant already knew after playing on the Team 180 club lacrosse team with Ames’ daughter, Bella.

The two met up at a library, where Weant finally was able to just talk about everything going on inside.

“I just felt comfortable around her, she was somebody I felt I could be around and be totally myself,” Weant said. “I felt completely comfortable around her.”

As she does with all her athletes, Ames made sure Weant knew she should never shy away from reaching out if she needed something. They continue to talk occasionally — Weant is now a sophomore at the University of Colorado-Colorado Springs — and Weant has seen her life change in major ways.

“The main thing for me is that I started feeling like myself again,” Weant said. “School became more enjoyable, I liked going to football games and hanging out with people again. I also got into a relationship and I felt like I could be in one again, like I could be myself and I wasn’t hiding.”

Weant also hopes that mental health becomes more of a focus in high school athletics, as she feels like the best capabilities of every athlete could come out if they are able to be in a good place with their mental health.

Ames also has helped a current high school basketball player — who asked to remain anonymous for the purposes of this story — to get back into a better place.

Some athletes identify themselves completely with the sport that they play and that was the case for his player, who said her reflection of self was 100% as a basketball player.

When she started to not see success with her play and also was surrounded by older teammates who weren’t the type that could help, she got into a bad place, even saying she felt pain physically.

“I had never really felt alone in my life and at that time, I was so isolated from my team and I didn’t have anybody backing me up,” she said. “I couldn’t talk to anybody on the team because they were all over and I was afraid that if I opened up, it would get worse or if they could even understand. And then that went into my personal life.”

A neighbor knew something wasn’t right and told her, which led to her deciding to get connected with Ames.

Initially proud, she told Ames that she wouldn’t cry, no matter what they talked about. She was wrong.

“I was sobbing like two weeks later,” she said. “It’s hard work, but it’s really changed me.”

Slowly, she has worked on developing more of an identity rather than just a basketball player and it has made a big difference. It’s also having a ripple effect in her own family, as two younger siblings who are also serious athletes have begun to take steps toward dealing with their own mental health.

She wishes that an avenue to talk about her mental health had been available with her team and hopes that it does in the future for more athletes who could benefit.

“I’m at a loss for words, that would have changed my life,” she said. “I think about all of the teammates I’ve had and how their lives could have been different. It would have had an impact and it could change the course of so many lives.”

Stuck in a loop in the pool

Although certainly physical, swimming is a sport that has a large mental component.

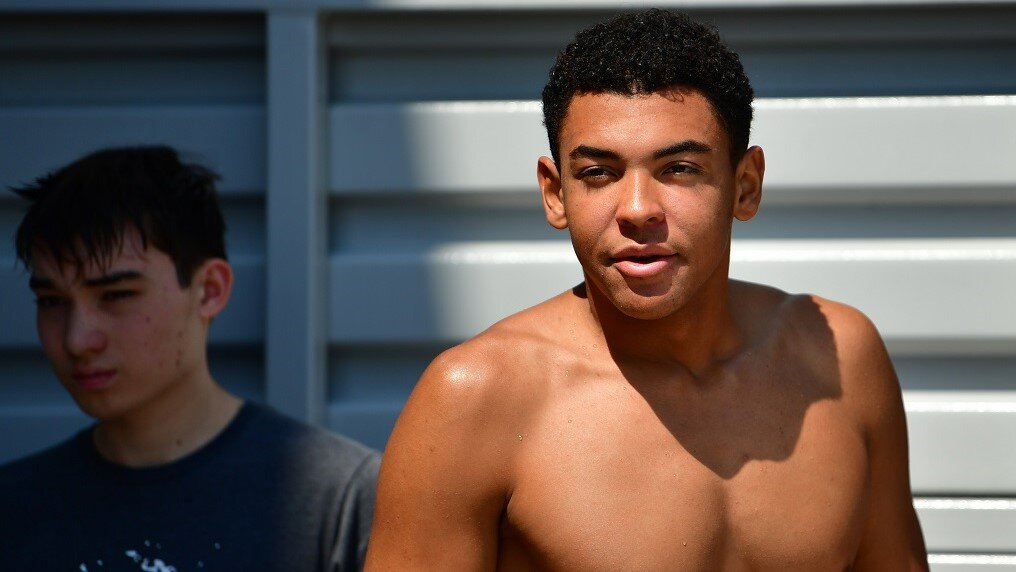

Hours of training in the pool with a lot of time to think can be a detriment, as Regis Jesuit senior Elijah Hawkins has found out. Hawkins has Ames — whose son Nick was his teammate on the swim team — as his counselor at school and found it easy to talk to her when things didn’t seem right for him.

“It’s hard because when it comes to practice, you can be in the water for two hours and bring things outside with you and they are there the whole time,” Hawkins said. “It’s not like a football or lacrosse practice where you can concentrate on other things. You can really bottle things up.”

Hawkins said that primarily, Ames has helped him compartmentalize his life, keeping separate what happens in his sport, at school and in his home life.

It has helped the totality of things — good or bad — not overwhelm him and has helped him focus on his performance as he is still relatively new to swimming with less than five years of competition under his belt.

Links to places to get help

Colorado Department of Human Services: https://cdhs.colorado.gov/behavioral-health/find-behavioral-health-help

Team USA: https://www.teamusa.org/MentalHealth

Ames' business to help athletes: https://www.thruthegame.com