How peyote — used as a ceremonial, legal medicine — helped heal one family’s grief

DURANGO, Colo. — This is my personal story of how my family and I utilize peyote as medicine.

Throughout the past several decades, the public has attached a negative connotation to peyote, most commonly identifying it as a drug. Calling this living entity — a cacti with hallucinogenic properties — a drug disrespects its purpose, and creates a barrier to those who use peyote for ceremonial purposes.

The American Indian Religious Freedom Act gives Indigenous people the right to utilize peyote during ceremonies.

The pandemic was very difficult for my family and myself. Something we were not prepared for was my father’s death from COVID-19. I found so much fear, anxiety and displacement after he passed, and so did the rest of my family.

My father passed away on June 12, 2020 and COVID-19 restrictions did not give my family the opportunity to have a peyote meeting at that time. It was not until October of 2021 that we were able to have our comfort meeting, or peyote meeting.

Peyote gave us strength to move forward in our individual lives and receive the proper healing that we were robbed of by the pandemic.

My documentary introduces me and shinalí — or paternal grandmother — Alice L. Bahe as participants of Azee Bee Nahagha of Diné Nation, formerly known as Native American Church.

We use peyote during our ceremonies, which usually take place at night. It is a sacred process that we adopted from the Northern tribes of the United States.

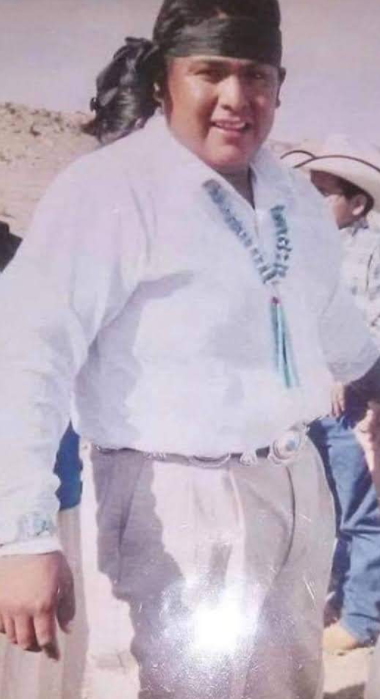

The Navajo Nation has more than 1,600 confirmed deaths from COVID-19 reported on the Navajo Nation Department of Health website and this story provides a closer look at what it was like for me and my grandmother to lose my father, Dewayne Aaron Labahe, and what it took to help us grieve.

Amber Labahe is a student at Fort Lewis College in Durango.

Do you have a story you'd like to submit for Native Lens? Learn more here.