Indigenous mural helps create a safe space for survivors of domestic violence

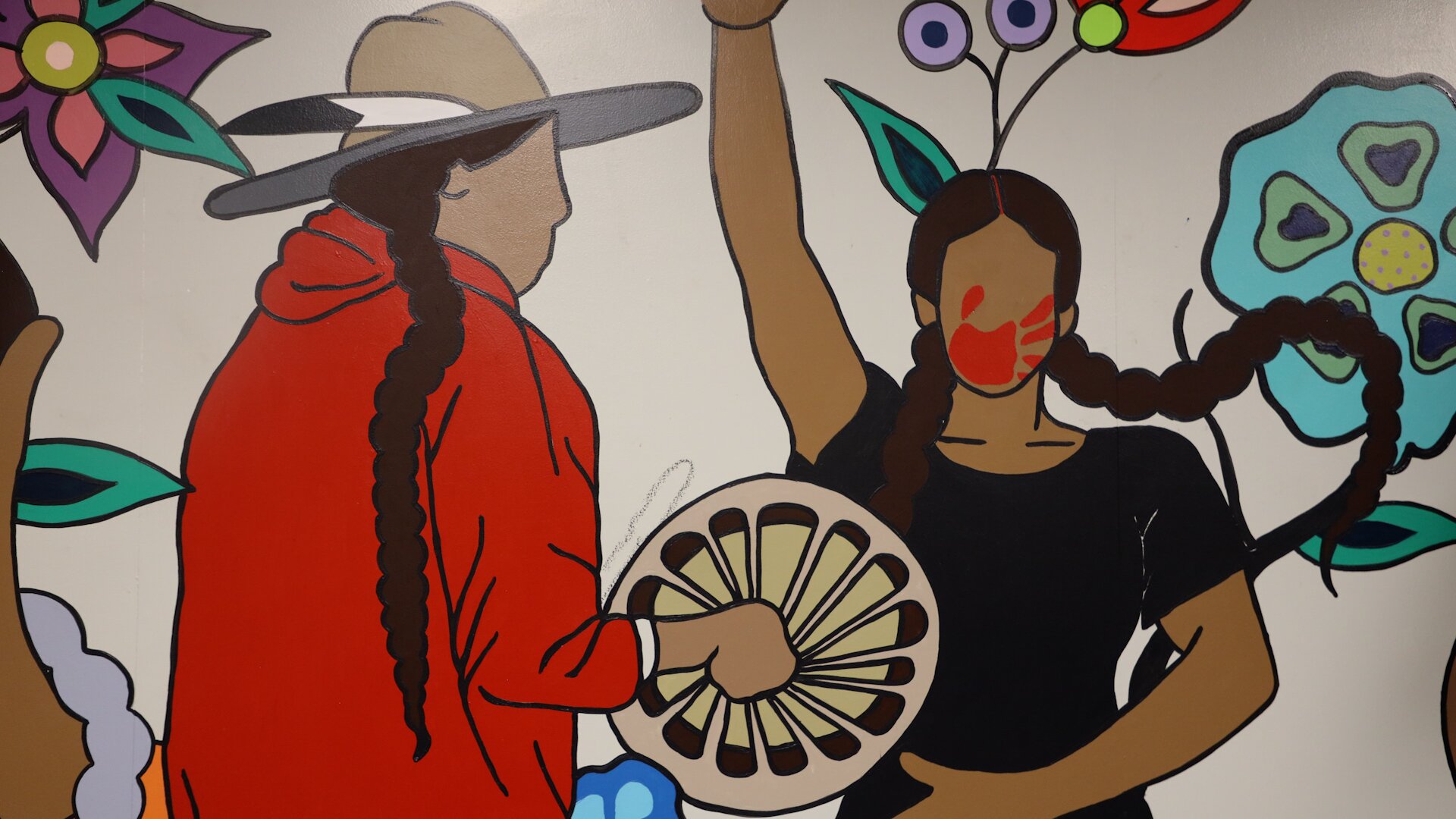

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — The first thing you notice when you look at Danielle Seewalker’s murals are the eye-catching, bold colors. Bright red, orange, blue, purple.

“I love color. I use almost every shade of color in a lot of my murals,” Seewalker laughs.

Look closer and you start to notice her colorful figures are missing a few details.

“I get a lot of questions about, ‘Why don’t the faces have any details on them? Why are there no eyes, are you going to paint eyes?’”

In fact, Seewalker leaves the faces she paints blank on purpose. Her distinctive style borrows directly from Indigenous history.

“The style that I tend to use in a lot of my murals stems from what plains Natives used to call ledger art,” says Seewalker.

Ledger art was a Native art form traditionally done on animal hides or cloth. It flourished from the 1860s to the 1920s. The term comes from the accounting ledger books that were a common source of paper for Plains Natives during the late 19th century. The style is known for being more simplistic and lacking fine details.

“In ledger style there were no details like that because it wasn’t focused so much on the skill of the artist, it was more focused on what was happening and documenting a story,” says Seewalker.

Seewalker uses the style to paint mostly Native figures, using her own Sioux heritage as inspiration to share Indigenous stories. The mural she is painting is at the office of Haseya, an advocacy program that serves Indigenous survivors of domestic and sexual violence in the Colorado Springs region.

The program offers community events, a free clothing pantry and resources to help survivors. Their leaders and members also participate in advocacy work and Native-specific legislation across the state. Monycka Snowbird is the program director.

“We’re not just healing from gender-based violence, we’re healing from generational trauma, and that was one of the reasons we wanted to bring Danielle in to do our mural here,” says Snowbird. “She’s a very well-known, very talented artist that isn’t just painting about these things, she’s actually doing this community work.”

The Haseya Advocacy Program moved into their new office in May of 2022, and they began envisioning a space that would immediately feel welcoming to Native people. Seewalker’s mural, which is visible from the hallway, was a big part of that plan.

“When [Native] people walk in the door, they immediately know this is a space for them, this is an extension of a home, and we’re here to uplift and empower our community” says Snowbird.

Seewalker’s mural features three scenes, each representing a different part of Haseya’s advocacy work. On the left, an elder woman in a bright orange shirt hugs a child that could represent her younger self. Her shirt symbolizes “Orange Shirt Day,” which falls on Sept. 30 and promotes awareness around Indian boarding schools and their negative impact on Native American communities.

[Related: Colorado Voices: An Indian Boarding School]

“There isn’t a Native American that exists today that hasn’t been touched by boarding schools,” says Seewalker.

In the middle of the mural, a warrior man beats a drum, supporting a woman from the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relative (MMIR) movement. The red handprint across her face is a symbolic representation of the violence that affects Indigenous women across the continent. The man in the scene is particularly important to Haseya because he represents their new IMPOWERED men’s program.

“We’ve realized if we’re only working toward healing our women, we’re not healing our community as a whole,” says Snowbird.

On the right side of the mural, a woman cradles her baby.

“It represents the healthiness of parenthood and the generational knowledge that we’re trying to pass to our younger children,” explains Seewalker.

Steven Moon, the coordinator for Haseya’s new IMPOWERED men’s program, is a fan of Seewalker’s contemporary take on the historical ledger art style.

“It’s today,” says Moon. “It’s not a depiction of Indigenous people wearing buckskin and standing around a fire. This is who we are and how we live.”

As Seewalker is finishing up the mural, she and Snowbird take a step back to admire the work. You can see the pride in Snowbird’s eyes.

“I don’t know how she was able to take these very large statements and issues that we gave her and condense it down into this mural, but she did it,” beams Snowbird. “And it’s perfect."

Alexis Kikoen is the senior producer at Rocky Mountain PBS. You can reach her at alexiskikoen@rmpbs.org.