Wage Investigations a Steady Issue for One of Colorado’s Oldest Employers

Ward Boydstun misses his teeth. The 27-year-old left his dentures at the Bradley Petroleum gas station when he was escorted out in handcuffs two years ago.

The company had paid for the new set of teeth for the former “manager of the month” when years of poor dental care left him with none.

Then, $4,534 and change was missing.

In a police statement, Boydstun wrote that he was covering cash register shortages that had occurred over four months. “I would pay money out of my own pocket … but it was too much. I went as far as asking my family to help me pay back the shortage.”

Boydstun admitted to the detective that he subsequently hid the shortages through accounting tricks.

More than 30 years of public records and internal documents dealing with Bradley Petroleum, one of Colorado’s oldest employers, show the company has repeatedly been investigated for violating federal and state labor laws, Rocky Mountain PBS I-News has found. In particular, for a pattern of suspending employees for shortages, reporting them to the police for alleged theft, and then permanently withholding the employee’s final check despite a lack of evidence of any wrongdoing.

I-News also interviewed 15 current and former employees at Bradley Petroleum and Sav-O-Mat and they commonly referred to policies that implicitly encouraged employees to pay out of their own pockets for shortages.

State and federal labor authorities have investigated complaints numerous times during the decades and recovered thousands of dollars in lost wages for Bradley workers. Under state law, employers are allowed to withhold wages for 90 days pending the outcome of police investigations. If no charges are filed, wages must be remitted plus interest.

Bradley Petroleum president Buzz Calkins said it was not the company’s policy to violate the state law, but he did acknowledge errors in processing final checks.

“If there are no charges filed, then their check is returned to them and they’re free to go on with their lives,” Calkins said in an interview with I-News.

Dozens of civil lawsuits are filed every year in Colorado courts for disputes over wages. Every year the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment receives an average of 5,000 complaints and collects $1 million in unpaid wages from across state industries.

Federal investigators have completed investigations into 22 gas station/convenience stores since 2005. In that period, Bradley Petroleum has been investigated twice.

In that respect, Bradley is not unique.

What makes the case of this local, family-run business notable is the consistency and longevity of the attempts in civil courts and by state and federal authorities to enforce wage laws in favor of Bradley’s workers.

Bradley has not been charged in criminal court, despite concerns and claims that the company’s long established pattern of withholding constitutes a form of wage theft. In fact, no Colorado employer investigated by the state has been charged in criminal court under the state’s wage laws since 2001, according to an I-News review of court data from 2000 to 2014.

Last year the Colorado legislature passed a law to strengthen the state Department of Labor and Employment’s process to investigate worker complaints and collect unpaid wages through an administrative process. Criminal provisions in a 2013 version of the bill were stripped out following opposition from business.

A Family Run Business Since 1912

Bradley lays claims to the first gas station in Denver, which opened in 1912. Known for cheap gasoline, third generation owner Brad Calkins has said in published interviews that he tries to undercut the competition.

The company operates 48 gas stations under the Bradley and Sav-O-Mat names throughout Colorado, Wyoming and New Mexico. It recently opened two Dunkin’ Donuts franchises.

“I don’t think you can stick around for 100 years if you’re a complete jerk,” he said.

Sometimes at the end of the shift at the gas stations, he said, the cash register and inventory don’t balance out. The quantity of cigarettes, lottery tickets or gasoline on hand is less than what the ledger says it ought to be.

Current and former employees cited many reasons that shortages occur. Customers drive off without paying, the credit card equipment malfunctions, and employees make mistakes. Outright theft by a customer or an employee also happens.

“That’s the nature of the industry,” Buzz Calkins said.

“I don’t think you can stick around for 100 years if you’re a complete jerk.” — Buzz Calkins, president of Bradley Petroleum

Shortages are at the heart of many employee disputes with Bradley.

I-News reviewed records from courts, law enforcement and the company from 1981 until November 2014 that show a recurring pattern: A shortage is discovered at a store, an employee pays out of pocket to cover it. Otherwise the employee is suspended, a manager calls local law enforcement to file a police report against the employee, and the employee does not receive his or her final check, contrary to the 90-day stipulation under state law.

Long Litany of Official Intervention

In 1981 the federal Department of Labor issued an injunction against Bradley and ordered the company to pay $6,000 for amounts “allegedly due” for violations under the Fair Labor Standards Act, and enjoined the company from retaliating against employees for filing complaints.

In 1992, Brad Calkins again signed an agreement with the federal Department of Labor to pay $8,293 to 44 employees to settle claims of alleged violations of federal wage and hour laws, while denying any violation of the law.

In 1997 the company agreed to another settlement, this time with the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment for $20,000 for the same pattern of firing employees for shortages and withholding their final checks upon filing a police report.

Four years later a Bradley worker from a Fort Morgan store filed a class action lawsuit for the same problem. In 2003 Bradley agreed to pay $80,000 to dozens of employees to settle the claims in the lawsuit.

However, Bradley continued to deduct wages from current and terminated employees. A court-ordered audit following up on the 2003 settlement shows the company withheld over $61,000 in wages from over 800 minimum wage employees for shortages and the cost of uniforms in 2007 and 2008.

The company had asked employees to sign a document that said the employee had taken the money and agreed to have the amount deducted from their paycheck. Some employees crossed out the words, “I took,” and added handwritten messages asserting their innocence.

“Ultimately it was decided that our policies are legal and that we do everything to act in good faith.” — Buzz Calkins, president of Bradley Petroleum

The judge presiding over the case showed frustration over the persistence of the company’s wage activities, “… even if there is no deliberate bad faith on the part of Bradley, I still have substantial concern that somehow the corporation or its minions don’t get it.”

In an email to I-News responding to the judge’s words, Buzz Calkins wrote, “Ultimately it was decided that our policies are legal and that we do everything to act in good faith.”

But in that December of 2009 ruling, the judge found that Bradley’s withholdings and employee-signed documents violated wage laws.

Buzz Calkins said employees were paid back for illegal deductions in 2007 and 2008.

Current Bradley employees are no longer required to sign the forms in the event of shortages.

In an April 2009 hearing, a former Bradley counsel articulated the new company policy: “… if there is a shortage of $10 or more in anything, lottery tickets, gas, cigarettes, cash, the employee is immediately suspended for ten days during an investigation.”

“Even though the policy says $10,” Buzz Calkins said, “we try to use discretion and have flexibility on terminating people with smaller shortages and try to give employees the benefit of the doubt.”

Current and former Bradley managers and cashiers say this policy leads to employees, and their bosses, fronting cash for mistakes so the employees can keep their jobs.

Ward Boydstun, the manager arrested for a shortage, said he didn’t want to fire his employees and have to cover their shifts, so he started paying for shortages instead of telling his supervisor.

Jacque Porter, Boydstun’s former boss, worked at Bradley for nearly eight years as a store and district manager. She said she had also paid the amount of a shortage to help out staff she believed to be honest.

“People are human beings, they are going to make a mistake,” Porter said. “If you’re making $8 an hour, you don’t have money to pay back that mistake.”

Former employees and managers who worked at stores in Delta, Commerce City, Thornton, and Englewood agreed.

Rick Scholl worked at Bradley for four years in payroll and as a district manager. He estimated he spent around $3,000 out of his own pocket.

“I’d say, ‘Let’s just put the money in to save the employee their job,’” he said.

Buzz Calkins said company policy does not accept or condone employees paying for shortages. “Absolutely not,” he said.

The company’s job application contained a clause that stipulates that prospective employees “agree to be responsible for all loss, including those occurring by theft, burglary or robbery,” and to repay them with 18 percent interest and attorney’s fees.

In an email to I- News on Dec. 18, Buzz Calkins wrote the company’s job application was being revised. As of Jan. 6, it no longer included the wording on repaying losses with interest and attorney’s fees, but still included the “responsible for all loss” statement.

Buzz Calkins did not respond specifically when asked if company policy left employees with little choice other than to cover shortages when faced with suspension or firing.

In 2010, federal investigators found that employees in a Delta store routinely covered shortages, despite a company policy prohibiting it. Three prior investigations had found the same problem.

“Every employee that was contacted during the investigation, including current and former managers, acknowledged that the practice of paying back cash register shortages in cash rather than be suspended occurred on a regular basis,” according to federal documents.

In an affidavit, former Bradley human resources manager Mark Schlueter said he wasn’t able to release an employee’s final check unless the aggrieved employee filed a complaint for unpaid wages with the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment, even if the company had no evidence of theft.

Buzz Calkins denied that was the policy.

“I don’t look at it as an epidemic or a systemic problem we have in the company,” he said. “It’s not intentional, it’s a mistake you have when the company gets to the size it is.” Bradley employs around 550 people, he said.

Buzz Calkins agreed that the company has a history of such “mistakes.”

Employees have complained about Bradley to state labor investigators more than 280 times since March 1997, according to affidavits by Colorado Department of Labor and Employment division chiefs. Since 2011, the department received 32 complaints, and repaid all but four.

“Absent bankruptcy or companies failing … I’ve received and worked on more complaints against Bradley Petroleum than any other employer,” Amanda Neal, former department compliance officer said in a September 2009 court hearing, according to transcripts.

State labor authorities do not have the technical ability to systematically analyze data on complaints. But Bradley has had more complaints against them than “several large grocery chains,” based on the limited comparison the state can do, spokeswoman Cher Haavind said.

The allegations of Bradley’s wrongdoing keep coming. Last year another class action lawsuit was filed in Weld County court for the same pattern of terminating employees over shortages and failing to pay their final check. Bradley attempted to have the case dismissed on the grounds that, through a clause in their job application, workers agreed to resolve disputes through arbitration, rather than through court action. The case is pending.

As recently as last November, managers at Bradley and Sav-O-Mat gas stations in Colorado and New Mexico filed police reports against employees over alleged theft. One manager interviewed by police said there was no reason to think the employee stole anything.

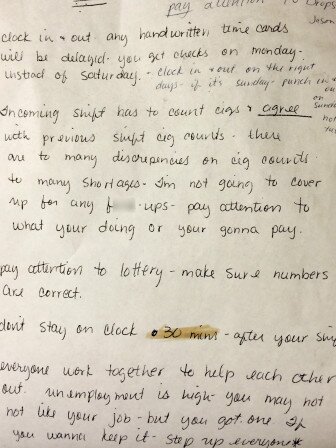

In November, I-News received a photo of a poorly-spelled handwritten note posted in the backroom of Bradley station in Westminster that warned employees to “step up” if they wanted to keep their jobs.

Buzz Calkins said he was surprised to see a photo of the note shared with him by I-News.

“This is just crazy,” he said, shaking his head. “This is intimidation.”

“Held Check Meetings” Alleged

Thousands of workers have cycled through positions as clerks and managers for Bradley and Sav-o-Mat – some sticking around for a few days, and others for years, according to court records and the company’s figures.

At the end of their employment, sometimes employees’ names ended up on the agenda for a “held check meeting” covering withheld final checks, said former human resources manager Schlueter.

Back in October, 2010, former cashier Daniel Terrones was number 15 on the agenda, according to a document shared with I-News.

In 2010, a manager said Terrones’ drawer came up $50 short and he was suspended. In an interview in December, Terrones said he still had not received his final paycheck, nearly a week’s wages.

The meeting notes feature the comment, “No Police Report filed because of lack of evidence” next to Terrones’ name.

Terrones’ girlfriend, Lisa Chavez, was also fired from Bradley after being accused of stealing $300.

Chavez, who now works at a poultry plant, filed a claim with the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment.

“I could not believe it,” Chavez said. “I fought it because I was innocent.”

Neal, then a state labor department compliance officer, contacted Bradley HR manager Schlueter, who responded in a letter dated October 2010, enclosing a check for $396 for Chavez’s unpaid wages.

In the December interview, Buzz Calkins said he wasn’t sure what happened to Terrones’ last check, but said he would repay it with interest. As of Jan. 13, Terrones had not received it.

Last Check Two Years Late

Almost two years to the date from Ward Boydstun’s arrest, Buzz Calkins said he was surprised to discover Boydstun’s final paycheck in a manila folder at corporate headquarters. The company responded to an inquiry from I-News by looking into Boydstun’s missing check.

A light blue check for $447 dated Dec. 14, 2012 sat on top of a stack of papers and Boydstun’s police report.

“We obviously made a mistake,” Buzz Calkins said, vowing to pay back the check with interest. But he isn’t convinced that Boydstun never stole the money even though the case was closed on January 15, 2013 for lack of probable cause.

Boydstun said the record of felony arrest has prevented him from getting another steady job. At times he has driven a cab or sold his plasma to earn money, he said.

Unable to pay rent, he stays at his mom’s or a friend’s house. Short on food money, he started volunteering at a cat shelter to be eligible for state assistance.

Boydstun was “very shocked” to learn that Bradley still had his final check.

“It could have helped me in a hundred ways,” he said.

As of Jan. 13, Boydstun had still not received his final check.