The never-ending cycle of the mental health hold: How many M-1 holds does it take before a person in crisis can get real help?

Forrest Williams spent more than a year in the Arapahoe County jail -- not for any crime, but awaiting mental health treatment so the 25-year-old could be deemed competent to face charges of threatening Judith Wilson, Williams' mother.

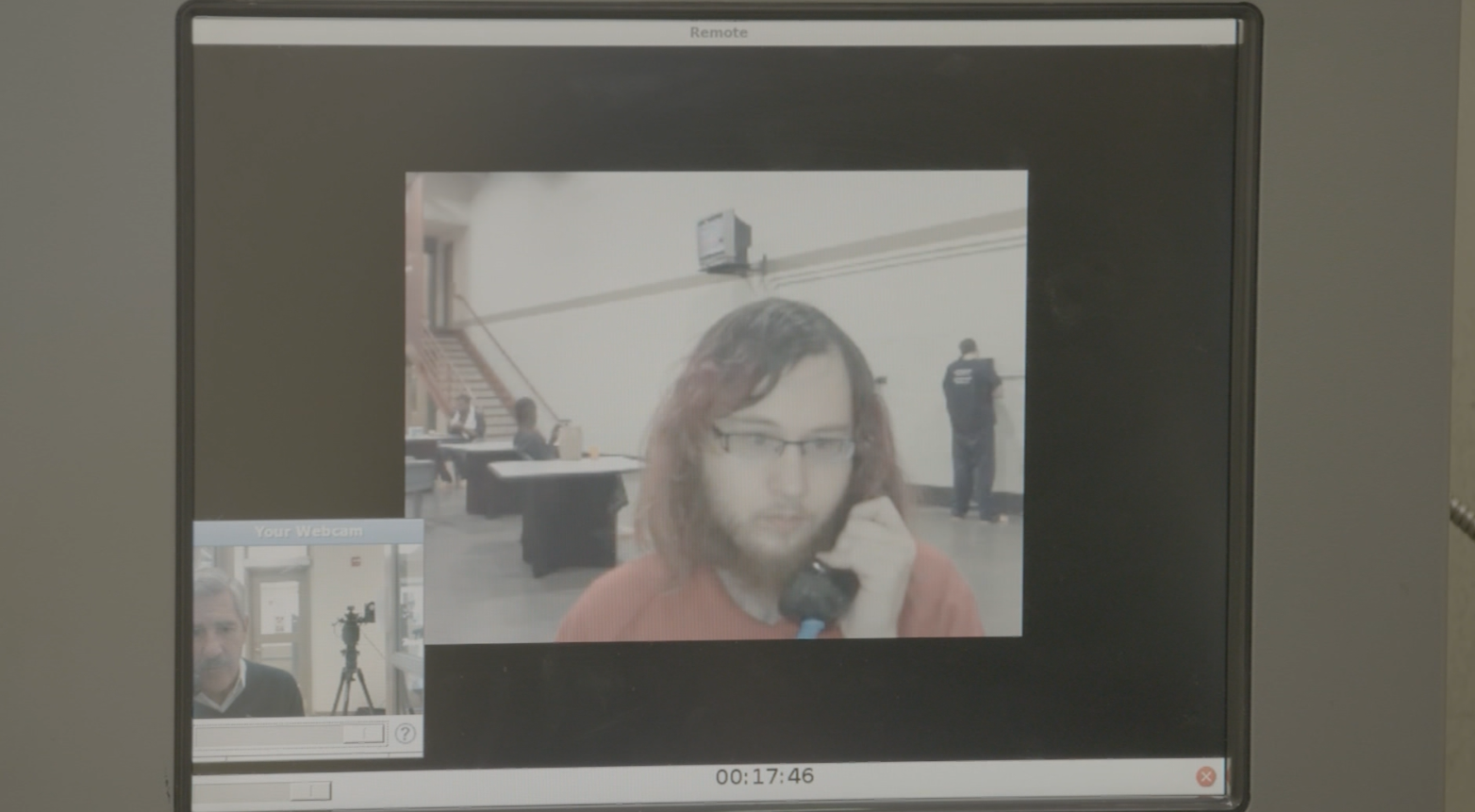

“I have had multiple suicide attempts here,” Williams describes to a visitor through a video communication system in the county jail.

But that stability can be short lived as Williams can easily slip into an agitated or psychotic state. Williams already has been charged while in jail for punching and spitting on a guard for not seeming to know the difference between people who are transgender and transsexual. (Family members told RMPBS Williams identifies alternately between male and female and prefers to be addressed only by last name.)

It is unlikely the charges will stick. Williams has been judged mentally incompetent and has been waiting for an in-patient mental health bed in hopes of restoring mental where the court is hoping her mental health can be restored.

Meanwhile, what Williams sometimes feels is intense:

“Depression to the point of rage,” Williams said.

It is a feeling Williams' mother knows well. Judith Wilson has been dealing with Williams’ intermittent psychosis since Williams was six years old. And last year, Judith Wilson feared for her life when Williams held a butter knife to her face.

“I had a cut on my cheek...from just pressure from the butter knife,” she said.

Her call to police was one of more than a dozen in the past two years when Judith simply could not control Williams and did not know what to do. Each time, Williams was taken in on a mental health hold for emergency treatment, joining more than 30,000 Coloradans in 2018 who were taken in by police on such holds because they are not getting the long-term mental health services they need. And for Williams, the incidents became more frequent.

“I couldn't get him into the doctor,“ Judith Wilson said. “Or if I did have an appointment, there are times I couldn't get him there and I couldn't safely drive him there because he was psychotic.”

And that would prompt another call to the police.

“So then he'd go on the M-1 hold,” she said. “But then they’d only keep him for a little bit or switch up his meds, send him home, and then it would escalate again.

She says there were times Williams was sick enough to need inpatient care, but it simply wasn’t available.

“They’d call around to the different inpatient facilities pretty much in the entire state,” she said. “And I mean we normally stay on the front range, but there's times that he's been in Fort Collins. There's times he's been put in Colorado Springs. There's other times he's just been down the street. It's just whoever has a bed available.”

But Judith says he would never be kept long enough to make a difference.

“He wasn't stable,” she added. “He wasn't functional, and not where he needed to be.”

So, the cycle would simply begin again. It wasn’t until Williams threatened Judith with a knife that Williams was finally taken from Judith’s home to jail.

Arapahoe County Sheriff’s deputy Chris Donovan has been to Judith’s house many times to respond to her calls for help, including the day Williams was arrested. He says Williams needs mental health services, not a jail cell. But Donovan also knows that often, being arrested is the only way for the mentally ill to get the long-term services they need. For him, that is frustrating.

“Would it be fair for someone with cancer to not get the proper treatment?” asked Donovan. “No. People would be up in arms. So I don't think it's fair for these mentally ill people, that there's not enough resources, there's not enough facilities for them to go and get the proper treatment.”

And like police and sheriff’s deputies across the state, Donovan interacts with those in need of mental health services, like Williams, on a daily basis.

“It's frustrating that ultimately [Williams] had to commit a crime to get help that he needs,” he said.

Williams, like dozens of others around the state, languished in jail, not getting proper treatment, waiting for bed space in a state mental health facility where they can receive long-term treatment to restore their competence. A judge has ruled that they do not need to be in jail, yet in Colorado that is the only place to keep them while they wait for inpatient services.

And for their families, it is both frustrating and a relief that their loved ones are finally on a path to eventually get help, albeit a detour through jail that they feel should not be necessary. After more than a year of waiting, Williams is finally on that path, having been moved to the state mental hospital in Pueblo.

“I feel terrible saying this,” said Judith. “But I am relieved that he's somewhere being watched and I don't have to do that anymore.”

If you need mental health services, contact Colorado Crisis Services for confidential support: 844-493-TALK (8255) or text “TALK” to 38255.